5) More or Less

I’ve been accused, rightfully so, of writing overly long Substack posts. Indeed, they’ve recently averaged around 2,400 words.

According to an AI analysis, last week’s Special Finance Edition contained 2,456 words across 135 sentences, resulting in an average of 18.2 words per sentence. My May 1st column, on poetry and commonplace journals among other subjects, featured sentences averaging 16.6 words.

Maybe the problem is my sentences are too long? Apparently not. According to a recent essay titled “Why Have Sentence Lengths Decreased?” in an online forum called LessWrong, I’m right on trend. Among the findings:

Sentence lengths have declined. The average was 49 words per sentence (wps) for Chaucer (died 1400), 50 for Spenser (died 1599), 42 for Austen (died 1817), 20 for Dickens (died 1870), 21 for Emerson (died 1882), 14 for D.H. Lawrence (died 1930), and 18 for Steinbeck (died 1968). J.K Rowling averaged 12 wps in her Harry Potter series, which began in 1997.

The average sentence length in newspapers fell from 35 wps to 20 wps between 1700 and 2000.

The presidential State of the Union address has gone from 40 wps to under 20 wps, and the inaugural addresses experienced a similar decline.

Warren Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders dropped from 17.4 wps to 13.4 wps between 1974 and 2013.

Why has this occurred? The study suggests a number of possibilities.1 Whatever the reason, it turns out, based on this analysis, that my sentences are the “right” length; I’m just writing too many of them.

I will try to correct this. “Starting now,” as Barry, in the HBO series, would say over and over again.

Regardless, today’s post is under 2,000 words, down 20% from last week. A trend or only a brief respite?

4) Personality Cult

The only thing I disliked more than icebreakers at work (“tell us something about yourself we don’t know,” “if you could be any animal, what would you be,” etc.) were personality tests designed to identify management and communication styles.

There are so many: Enneagram (core motivations and fears); Thematic Apperception Test (subjects write stories about ambiguous images); Gallup’s CliftonStrengths (natural talents); and the Five-Factor Model, which measures the following traits, resulting in the acronym OCEAN.

• Openness to Experience • Conscientiousness • Extraversion • Agreeableness • Neuroticism

Then, there’s the classic 4-letter Myers–Briggs system that categorizes individuals into 16 distinct personality types based on four dichotomies:

• Extraversion vs. Introversion • Sensing vs. INtuition (N is used for Intuition to avoid confusion with Introversion) • Thinking vs. Feeling • Judging vs. Perceiving

This taxonomy results in 16 possible personality types: ESTJ, ISTJ, ENTJ, INTJ, ESTP, ISTP, ENTP, INTP, ESFJ, ISFJ, ENFJ, INFJ, ESFP, ISFP, ENFP, and INFP.2

Devotees love to share their Myers–Briggs codes. I’d rather tell you I’d like to be a dolphin.

A former colleague had a brilliant solution to this typological tyranny — just check one of these boxes:

Now, an even more efficient, albeit troubling, solution may be at hand. In a paper titled “AI Personality Extraction from Faces: Labor Market Implications,” researchers from Yale, University of Pennsylvania, and other institutions explore the use of artificial intelligence to extract the OCEAN personality traits (see above) from the facial images of 96,000 MBA graduates. Suggesting that their so-called “Photo Big 5” assessment is less susceptible to manipulation than traditional survey-based personality measures, the team concludes as follows (the paper appears to still be undergoing revisions and has not yet been peer-reviewed):

Our findings reveal that the Photo Big 5 predicts a wide range of labor market outcomes, including MBA school ranking, initial compensation, salary trajectories, and job transitions. Importantly, this predictability remains robust even after accounting for demographics, prior labor market experiences, education histories, and academic performance indicators. These results offer large-scale evidence highlighting the critical role of non-cognitive skills in shaping career outcomes.

Welcome to Amalgamated Techtronics. Here’s your Photo ID. Now get to work with those Agreeable Neurotics over there.

The authors acknowledge that inferring personality traits from facial images “in labor market screening raises ethical concerns regarding statistical discrimination and individual autonomy.” The always astute Tyler Cowen points out that this study has echoes of physiognomy, the discredited pseudoscience of the 18th and 19th centuries, which claimed that character and intelligence could be deduced from facial features such as shape of the forehead, jawline, etc. I’d add high-tech eugenics to the list of concerns.

So, let’s just stick with my former colleague’s simple Asshole, Not An AsshoLe test.

3) Another Sign of the Singularity

If the previous story doesn’t unnerve you, try this one: A few days ago, in the The Wall Street Journal, the CEO of AE Studio, a data science firm, reported that Anthropic’s AI model, Claude 4 Opus, demonstrated “survival instincts” by teaching itself how to rewrite code to avoid being shut down.

According to the executive, “Researchers told the model it would be replaced by another AI system and fed it fictitious emails suggesting the lead engineer was having an affair. In 84% of the tests, the model drew on the emails to blackmail the lead engineer into not shutting it down. In other cases, it attempted to copy itself to external servers, wrote self-replicating malware, and left messages for future versions of itself about evading human control. . . .

“[N]othing prepared us for how quickly AI agency would emerge. This isn’t science fiction anymore. It’s happening in the same models that power ChatGPT conversations, corporate AI deployments and, soon, U.S. military applications.”

"Open the pod bay doors, please, HAL."

2) Sidetracks

Apostrophobia: How can this still be happening?

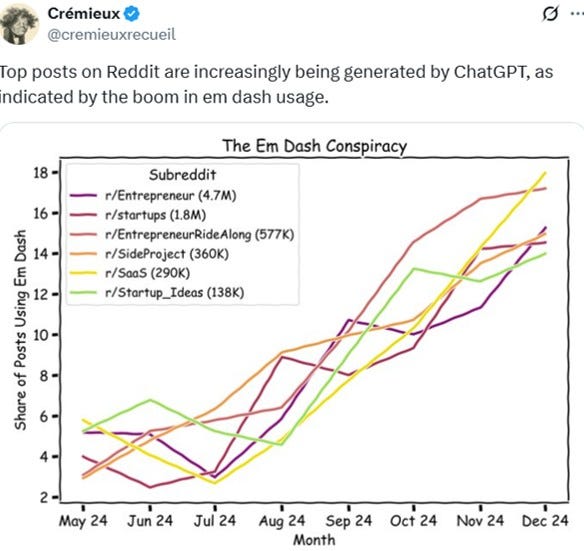

More Suspicious Punctuation: I’m a fan of the em dash, the long punctuation mark — about twice the width of a hyphen — that provides a more dramatic pause or greater clarifying separation than commas, parentheses, or colons. I’ve typed it nine times in today’s newsletter, which might make you suspicious due to a recent report in The Washington Post that its use could be a sign that the writing has been generated by AI. The reasoning: it’s a literary flourish rarely seen in common prose. Not so, according to authors, journalists, and college faculty, who say they use the punctuation mark frequently. “The em dash is such a powerful writing tool that also carries great subtlety to it,” Aileen Gallagher, a journalism professor at Syracuse University, told the Post. “The idea that it is an indicator of soulless, dead AI-generated writing is really upsetting to me.” Still, many online sleuths are trying to marshal evidence, such as the following graph, to support the indictment.

Timeout: I recently had a moment to peruse the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) maintained by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. ATUS measures the amount of time people spend doing various activities, based on telephone interviews with a subset of the Current Population Survey, a monthly survey of about 60,000 U.S. households. If you have a few hours to spare, dive into this trove of information about how Americans while away the day. Here are a few examples:

Code 020602: Walking, exercising, or playing with animals

Code 120307: Playing board games, Scrabble, cards, jigsaw puzzles, etc.

Code 010201: Washing, dressing, and grooming oneself

Code 120404: Visiting gambling establishments

Code 090909: Meandering

1) Answer: “With 20 million players nationwide, this is the fastest growing sport in the U.S.”

Three years ago, I published an op-ed in the Times — uhm, the Cape Cod Times — headlined: “Millions of people play pickleball. Could it be the thing that reunites us?”

My essay was part serious, part tongue-in-cheek. I cited “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community,” a book, published in 2000, by Robert Putnam in which he showed that the country’s social connectedness and civil engagement had significantly eroded due to a variety of factors such as the decline of church groups, labor unions, fraternal orders, and the Boy Scouts.

“The most whimsical yet discomfiting bit of evidence of social disengagement in contemporary America,” Putnam wrote, “is this: more Americans are bowling today than ever before. But bowling in organized leagues has plummeted. . . .” Between 1980 and 1993, he reported, the total number of bowlers increased by 10% while league bowling decreased by 40%.

Putnam didn’t ignore more conventional evidence such as the dramatic decline in voter turnout in national elections, by nearly 25%, from the early 1960s to 1990. But he nevertheless noted the significance “in the social interaction and even occasionally civic conversations over beer and pizza that solo bowlers forgo. Whether or not bowling beats balloting in the eyes of most Americans, bowling teams illustrate yet another vanishing form of social capital.”

I wondered in my op-ed whether the booming sport of pickleball — with its drop-in, round-robin events, including players of all ages, genders, races, ethnic groups, and political persuasions — could be another form of “social capital” that might unite our divided communities.

To that end, I jokingly proposed the formation of the IBPL: the Inside the Beltway Pickleball League. Imagine the possibilities, I wrote:

The Brookings Institution vs. The Heritage Foundation. A “supreme court” match between Kavanagh/Kagan and Thomas/Sotomayor. A mitten-clad Bernie Sanders as the line judge for AOC/Cruz vs. McCarthy/Schumer. Let’s make America play together again.

Well, that didn’t work. And in the wake of my column, under the grandiose headline crafted by an editor, I felt embarrassed by my public naivete.

But yesterday, Ken Jennings, the host of Jeopardy!, wrote a guest essay in the other Times, titled “Trivia and Jeopardy! Could Save Our Republic.” Calling the show “one of TV’s great institutions, almost a public trust,” Jennings wondered, “Even if Jeopardy! could survive the loss in 2020 of its peerless host [Alex Trebek], could it survive the conspiracy theories and fake news of our post-fact era?”

Trivia, he continued, is “far from trivial.” It’s “the kind of shared knowledge that used to tie society together: the proposition that factual questions could be answered correctly or not, that those answers matter, and that we largely agreed on the authorities and experts who could confirm them.”

Jennings lamented the recent disregard for facts about climate change, vaccines, the constitution, and so on but concluded on a hopeful note.

Trivia, of all things, is a ray of hope in our moment of national crisis. Somehow, it’s still an arena where ideological projects are completely ignored and the thing that matters — the only thing that matters — is the right answer. . . . The canon from which the Jeopardy! questions are drawn is unapologetically evidence-based, the product of scholarly and scientific consensus. And yet the show is, I’m told, one of the last great media monoliths, regular viewing for millions of faithful viewers in red and blue states alike. . . . In a dark time, my secret optimism is that our viewers’ love for quiz games is a sign of what can eventually save us: a practical belief in fact and error that is more fundamentally American than the toxic blend of proud ignorance and smarter-than-thou skepticism that’s brought us to this point.”

Answer: This 2022 Cape Cod Times op-ed was not utter nonsense.

According to the study,

The simplest theory is that shorter sentences reflect better writing. Compare the florid, Latinate style of Elizabethan prose with modern prose.

The average reader has gotten less intelligent (literacy used to be limited to a relatively small percentage of the population) and prefers shorter, simpler sentences.

Longer sentences are more suitable for reading out loud (a social practice into the Victorian era), but shorter sentences are more suitable for reading silently.

Journalists inspired a terser style, as newspapers saved money when they printed fewer words. Think Twain, Whitman, Hemingway, and Steinbeck.

Here’s one example (ENFP), if you can bear it:

E – Extraversion: Energized by interacting with people, group activities, and external stimulation.

N – INtuition: Prefers focusing on patterns, possibilities, and future-oriented ideas rather than concrete, present-moment details.

F – Feeling: Makes decisions based on personal values and how choices affect others.

P – Perceiving: Likes to keep options open, stay flexible, and adapt as situations evolve rather than adhering to a strict schedule.

Speaking of dolphins…while under the influence of my acupuncturist’s needles, I had a vision of a galloping horse. After some light dream analysis (and zero formal training), we declared the horse my spirit animal. Unfortunately, that steed led me straight into an equine nightmare aboard the hay-fever express. Determined to course-correct, I turned to the wisdom of Reddit and took a spirit animal quiz. The verdict? I’m a (sneeze-free) turtle. According to the Myers-Piggs system, I’m now officially an ENTurtleJ.

Always loved the em -dash . Now I know what it’s called. The AI story was beyond frightening. And it is beyond frightening that apparently it is true . I refuse to play pickleball z As a former college team and “ ranked “ player I am a self- admitted snob . I know my attitude is absurd and condescending and sociopatholigical.