I had some extra time this week, so I was able to write shorter. You might be relieved to learn that today’s column contains 30% fewer words than my previous post.

But first, this generous blurb from ChatGPT, when I gave it the following prompt on April 27, 2025: “A guy by the name of Scott Sherman writes a Substack called ‘Meandering Tour.’ Can you please compose a parody of his weekly columns.”

“Scott Sherman’s Meandering Tour has a very particular style: it’s usually contemplative, a bit rambling in a deliberate way, mixing personal anecdote, literary references, and a slightly world-weary but affectionate tone toward the subject he’s covering. He meanders, yes — but you can tell it’s a crafted meander.”

ChatGPT went on to offer a rambling essay, supposedly in my style, titled “Reflections on an Overripe Banana and the State of American Letters.” I’ll spare you.

Now, back to the tour.

5) Poorly-Versed

The New York Times launched a lovely feature this week, called the “Poetry Challenge,” designed to promote the reading, memorization, and appreciation of poems. “A poem recited under your breath or in your head,” according to the introduction, “can soothe your nerves, drive away the noise of everyday life, or grant a moment of simple happiness.”

Unless you’re like me, in which case you can no longer memorize a damn thing, you get agitated when punctuation appears to be missing, and you find metaphors and similes unfathomable. (I do like onomatopoeias, though.) I’m not saying I don’t like poetry; I’m just poetically challenged, as I have difficulty understanding verse.

I should have realized I wasn’t cut out for poetry when I had trouble mastering analogies in SAT prep. BIG : SMALL as HOT : ? Obviously, the answer is COLD, but the choices were always something like this:

A) Pulchritudinous B) Heraldry C) Solipsism D) Contumely

“Scott, just pick the closest word,” urged Mr. Daniels, my 9th Grade English teacher, who also taught us the poem “Jabberwocky,” by Lewis Carroll. The poem begins as follows (and here I resort to Google):

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe.

If you’re going to use nonsense words like these right out of the gate, a literal thinker like me will inevitably pull up lame at the first turn.

Fast forward to this week’s New Yorker poems. The first, “Madrigal,” by Spencer Reece, begins like this:

Minnesota, I hardly know you anymore.

Who knows when grief ends--

if ever. The two who preoccupied me

have turned and gone through the door. I had a great deal of trouble following the thread after that. Near the end of the poem, there’s a reference to a young woman who wore “a Dr. Zhivago fur hat.” By then, I was completely lost — like Omar Sharif trudging across the frozen landscape in the movie itself.

My friend Becky is a poet. She gave a talk once to a group of friends, who meet regularly to discuss weighty topics. “I’m using notes,” she began, “because I am challenged by sequential thinking.”

“I digress,” she continued, “Constantly. I am entertained by a mind adept at metaphor and simile, but less adept at sticking to the point. Poetry presented itself as the system that was a good fit for my way of thinking.”

So, therein lies one of my poetic challenges: my grey matter is the exact opposite of Becky’s brain. I’m not wired to fully appreciate the art of poetry; I’m too much of a linear thinker.

My friend Nancy, also a poet, once wrote the following to me, when I was struggling to comprehend one of her poems: “You don’t necessarily have to totally understand it. Poems are meant to evoke emotions and associations.” A tall order for someone with my DNA.

Still, some verses, albeit usually straightforward ones, have lodged in my memory and inspired me over the years, especially these final lines from “The Municipal Gallery Revisited,” William Butler Yeats’s meditation on the museum portraits of artists, politicians, poets, and authors who helped shape modern Ireland:

Think where man’s glory most begins and ends And say my glory was I had such friends.

These words do, in fact, “soothe [my] nerves” and “grant a moment of simple happiness,” as the Times poetry feature promises.

But then I recall that Charles McGrath, former editor of the Times Book Review, once told Becky’s husband, “I’m one of eight people in the U.S. who read poetry but don’t write it.”

Yet onward I go.

4) What’s in a Name — or Three?

Can someone tell me why so many celebrities go by three names?

As I type these words, I can hear myself turning into the nasally curmudgeon Andy Rooney, the late writer who used to close 60 Minutes with a light-hearted commentary. He would typically began with a trivial question, such as “Do you ever wonder why baseball players spit so much?” and then meander through a whimsical explanation.

But my question surely is much more pressing, in face of moniker madness: Sarah Jessica Parker, Billy Bob Thornton, Jada Pinkett Smith, Helena Bonham Carter, Neil Patrick Harris.

I suppose adopting a triplet name is a way to distinguish oneself in the firmament of stars. But if a distinction becomes common, then it’s no longer differentiating.

My response has been twofold: 1) add as many triple names as possible to the charades pile to annoy certain family members on game night (you might recall I don’t like charades), and 2) keep track of the proliferation of such names, as a therapeutic outlet.

To that end, I have been compiling this (poorly) curated list, including historical figures, politicians, and assassins, and now numbering 152.

Please take a look and let me know who’s missing and what corrections should be made. Two categories are ineligible: hyphenated names, such as Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and non-hyphenated married names, such as Amy Coney Barrett.

3) “Take Two Aspirin, and Prompt Me in the Morning”

A new AI platform — Semantic Clinical Artificial Intelligence (SCAI, pronounced “Sky”) — recently achieved remarkable results on the three-part U.S. Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE), according to a paper published last week in JAMA Network Open. A team of researchers at the State University of New York at Buffalo found that SCAI achieved better scores than most physicians and all other AI tools.

“SCAI is different from other large language models because it can have a conversation with you and as a human-computer partnership can add to your decision-making and thinking based on its own reasoning,” explains Peter Elkin, M.D., lead author and chair of the school’s Department of Biomedical Informatics.

The platform can respond to medical questions posed by the public as well as clinicians, via this link. I decided to give it a spin, asked it a question about myself, and found its answers to be absurd, especially Option 5 below:

You: I am driven crazy by grammar, punctuation, and semantics. When I see or hear a language mistake, I feel the need to correct it or clarify it. It's getting in the way of my friendships and causing me to lose focus at work and in everyday life. I feel like I need some help. Do you have any suggestions?

SCAI: It sounds like you're experiencing a strong desire to correct language mistakes, which can be distracting and affect your daily life. Here are some suggestions that might help:

1) Recognize your triggers: When you notice yourself getting anxious or distracted by language mistakes, take a step back and try to identify what's triggering this response. Is it a specific type of error, a particular situation, or a certain person?

2) Practice self-compassion: Remind yourself that everyone makes mistakes, and it's okay not to correct every single error. You don't have to point out every mistake you see or hear.

3) Set boundaries: If you find that your desire to correct language mistakes is interfering with your friendships or work, it might be helpful to set some boundaries. For example, you could decide not to correct mistakes in social situations or focus on more important aspects of your relationships.

4) Find healthy outlets: Channel your energy into activities that bring you joy and help you relax, such as reading, writing, or discussing language-related topics with like-minded individuals.

5) Consider therapy: If your desire to correct language mistakes is significantly impacting your daily life and causing distress, it might be helpful to speak with a mental health professional. They can help you develop coping strategies and work through any underlying issues that may be contributing to your response. Remember, it's essential to find a balance between your desire to correct language mistakes and your overall well-being. By acknowledging your triggers, practicing self-compassion, setting boundaries, finding healthy outlets, and considering therapy if needed, you can learn to manage your response and improve your relationships and daily life.

Substacker, heal thyself.

In related professional news, the L.A. Times reports that 23 of the 171 multiple choice questions on the February 2025 California Bar Exam were developed with the assistance of AI by the bar’s independent, non-legally-trained psychometrician.

2) Sidetracks

80-Year Dash: Domenic Stellato, 82, won the 100-meter dash for men over 80 years of age, at the Penn Relays last weekend. (h/t Professor Capetta)

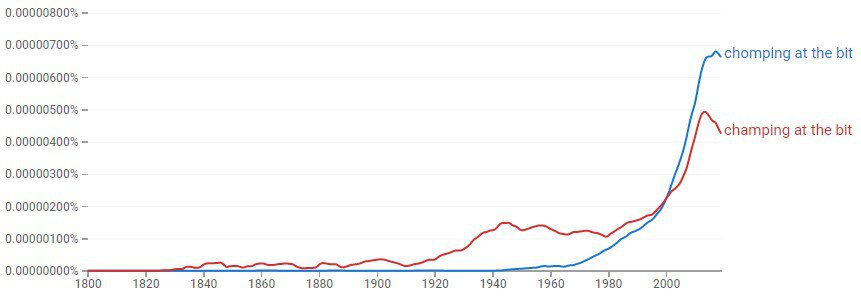

Bit Much: Last week, I published an exegesis of the difference between the verbs “careen” and “career.” (“Exegesis” is Latin for overwrought and overwritten.) At the end, I promised to unravel the linguistic puzzle that has perplexed so many for so long (well, my friend Garry and me, at least): When you want to describe a person who is impatient to get started or take action, do you say “chomping at the bit” or “champing at the bit” — a reference to a horse grinding the “bit,” or piece of metal, in its mouth. According to grammarist.com, the original expression was “chomp,” but “champ” has overtaken “chomp” down the stretch and is widely accepted in modern usage. NPR, citing the late language expert William Safire, agrees that “chomp” is outdated. Follow his lead, and don’t ride roughshod over the English language.

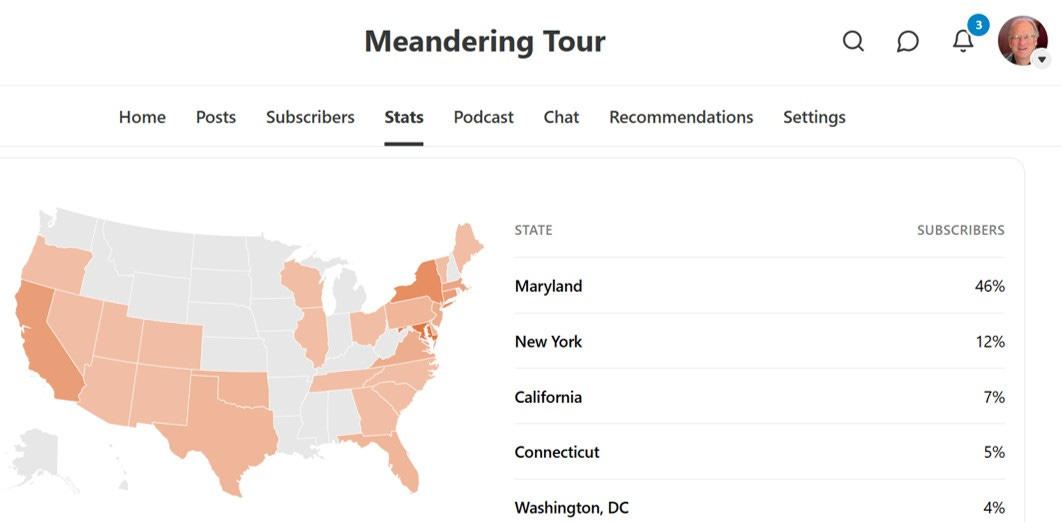

Global Impact: According to Substack, Meandering Tour is read across 27 U.S. states and 4 foreign countries, including Australia (2), Canada (1), Israel (1), and Kenya (1). (I once had many more readers outside the U.S., but the tariffs have hit me hard.) Inside the U.S., you can see from the Substack “dashboard” below that my readership (about 800 a week) is heavily bicoastal, although I seem to have meandered a bit into the Southwest. Five percent of my readers reside in the Nutmeg State, where one of its denizens, Colin McEnroe, recently published a column mentioning Meandering Tour, which, in all fairness, describes my Substack more accurately than ChatGPT above:

I don’t get what people mean when they say they don’t like country music. It came up also in a recent issue of the Meandering Tour Substack, which has recently emerged as America’s go-to newsletter about culture and neurosis, a kind of Rosetta Stone for the intersection of inquiry about the arts and humanities with untreated Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

Thank you, Colin. “Logrolling in Our Time,” anyone?1

1) Commonplace

About 15 years ago, I started compiling a “commonplace.” For the uninitiated, a commonplace is a kind of book, dating back to antiquity, for collecting aphorisms, proverbs, quotations, notes, and the like. Typically organized by subject and source, it is a way to keep track of insightful observations and treasured thoughts — an early form of database, if you will.

According to the ultimate commonplace, Wikipedia, in 1685, the English Enlightenment philosopher John Locke wrote a treatise in French on commonplace books (translated into English in 1706 as A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books) "in which techniques for entering proverbs, quotations, ideas, speeches were formulated. Locke gave specific advice on how to arrange material by subject and category, using such key topics as love, politics, or religion.” Examples of commonplacing (the use of this gerund seems to be commonplace) abound in literature. And such books figure prominently in literary analysis. The English poet John Milton, for example, kept a commonplace book, regarded as “an indispensable if slightly forbidding document” for “serious Miltonists.”

Today, commonplace merch is widespread. There are commonplace histories, blogs, YouTube videos, classes, and, of course, the blank-page books themselves for sale.

I keep my own commonplace on an app called Evernote, along with other records. Here are some of my favorite, short entries:

Grammar: “The greater part of the world’s troubles are due to questions of grammar.” — Michel de Montaigne

Law: "If you have the facts on your side, pound the facts; if you have the law on your side, pound the law; if you have neither the facts nor the law, pound the table." — Possibly Carl Sandburg

Music: “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” — Frank Zappa

Ocean: “The seaside is like that: one moment gaiety and laughter, the next sodden misery. A bit like show business. “ — Graham Swift, Here We Are

Research: “One must stop conducting research before one has finished. Otherwise, one will never stop and never finish.” — Barbara Tuchman

Work: “A real job means you shower at the end of the day, not at the beginning.” — Elliot Ackerman, Red Dress in Black and White

Work: “An old friend of mine, a journalist, once said that paradise on earth was to work all day alone in anticipation of an evening in interesting company.” — Ian McEwan, Machines Like Me

Voting: “A vote is not a Valentine, you aren’t confessing your love for a candidate; it’s a chess move for the world you want to live in.” — Rebecca Solnit

Give it a try. It can be as soothing as poetry yet simple and clear.

To my World Weary and Affectionate Meanderer,

I offer a few more 3 name people for your list: (didn’t check your list. Might be duplicates)

John Wilkes Booth

Kareem Abdul Jabaar

Corken Head Jones

Karl Anthony Towns

Gypsy Rose Lee

Glad post was shorter, even if it takes u more time.

Ray, my dad, would often read The Children’s Hour by Henry Wadswoth Longfellow (three names…) to me at bedtime. That poem was the genesis for “My List of Peeves” in my commonplace. Thanks to Henry, the first entry on that now long list is: Poems with forced rhymes.

The second and fourth lines of The Children’s Hour stanzas pair beautifully:

Feet / Sweet

Stair / Hair

Eyes / Surprise

Hall / Wall

Chair / Everywhere

Entwine / Rhine

Wall / All

Depart / Heart

Day / Away

All well and good. But, close to 70 years ago and to this day I have been peeved by the first stanza:

Between the dark and the daylight,

When the night is beginning to lower,

Comes a pause in the day’s occupations,

That is known as the Children’s Hour.

I used to be a regular churchgoer (not gower) and on Sundays the hymn We Plough The Fields, and Scatter by Matthias Claudius was a staple of the annual church rotation. The hymn contained three stanzas and one refrain with the following rhymes.

Land / Hand

Grain / Rain

Above / Love (Refrain)

Far / Star

Fed / Bread

Above / Love (Refrain)

Good / Food

Imparts / Hearts

Above / Love (Refrain)

In an otherwise respectable hymn, we get ambushed by Good / Food. I can’t imagine a time in the evolution of the English language when those two words ever rhymed. Seriously, Matthias? Sheesh.