5) Fondly Remembered

Life is like punctuation: It begins with a whimper and ends with an Interrobang1 followed by a comma.

Actually, “the comma” — a phrase sometimes used2 to refer to the part of an obituary headline, set off by commas, that identifies the deceased, as in this recent notice in The New York Times: “Val Kilmer, Film Star Who Played Batman and Jim Morrison, Dies at 65.”

These impressive examples also appeared in the Times last week:

One’s life summed up between two little dots with hanging tails. For Kilmer and other notables, it’s relatively easy.

But what about the rest of us? How would you distill your life into a handful of words. My pal Dan Okrent, an editor, writer, and baseball savant, predicts his “comma” will read as follows::

Daniel Okrent, who always said that he could bring peace to the Middle East and cure cancer but that his obituary would be focused on his invention of fantasy baseball, was right. He was 98.

My dear college friend Colin McEnroe, a writer and host of an NPR talk show in Connecticut, told me recently, “Every year we have talks at work about contest entries, and with each passing year, I care less. I tell my producers I'm just playing for my obit now.”3

I’ve been thinking about obituaries too, especially in the wake of so many recent Boomer-era celebrity deaths (Gene Hackman, George Foreman, Roberta Flack, David Lynch, the aforementioned Kilmer, et al.) — but not because I think that I deserve public recognition or that my departure is at hand.

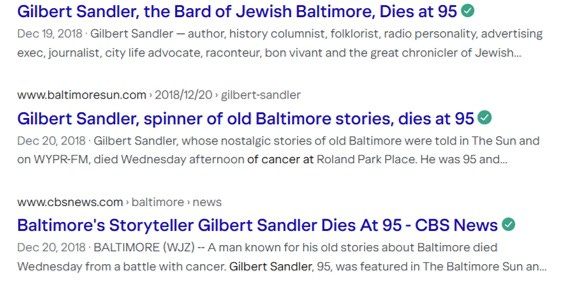

It’s because Gilbert Sandler, a lifelong friend and mentor who died in 2018 at the age of 95, always told me I would amount to nothing. “What have you accomplished, other than having a lot of different jobs?” he once said, when I was working in financial services after stints as a lawyer, journalist, consultant, and assistant medical school dean.

When I applied to the Maryland Bar, Gilbert (whose own “commas” above aptly reflect his warmth and humor as well as his professional achievements and community impact) sent me a copy of a letter he purportedly sent to the bar association. It began, “I must, with deep regret, respectfully decline to recommend Scott Sherman to you.”

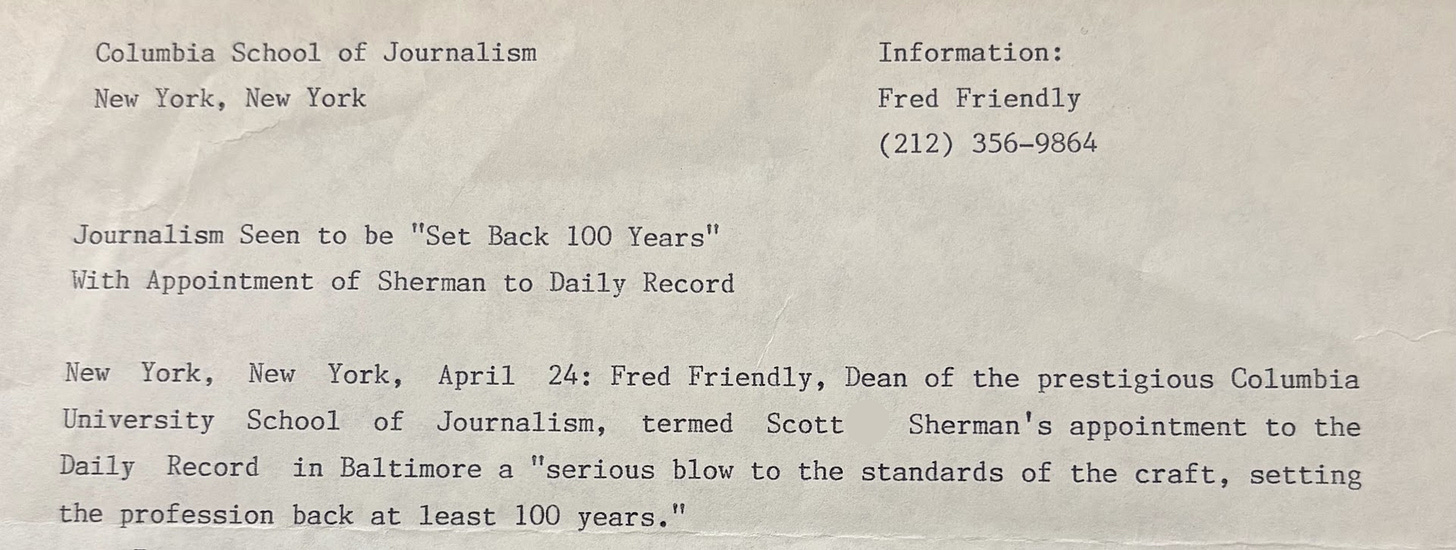

Some years later, when I decided to quit the law and try my hand at journalism, I received in the mail (that’s what we used to call it) a copy of a press release, which began like this:

The announcement continued, in part:

In a statement released to a hastily called press conference, Friendly said Sherman's "background was inadequate, scattered, and unpromising." Friendly called Sherman's early effort — a story about the resignation of the City Solicitor — "a fifth-grade piece of copy about a low-level employee that should be no more than a four-line mention in a personnel column. At best, it was overblown, overwritten, and boring."

And so it went every time I switched jobs, until that day, in the mid-2010’s, when Gilbert (so famous around town for wearing a pork pie hat that they put it in a museum) reprimanded me for being “unable to hold down a job,” adding, “What are they going to say about you in your obituary, for God’s sake?”

We discussed his concern over many meals together, until Gilbert finally came up with a solution about a year before he himself passed away: Scott Sherman, Serial Job Changer, Dies at XX.

I’ll always treasure that anticipatory tribute and the man who composed it.

4) As the Saying Goes . . .

Ed, another exceptional mentor, was fond of saying, “Where there’s an information vacuum, emotion fills the void.”

Ed also tried to teach me the “first rule of holes” — namely, “stop digging” — when, in the early days of my final job before retirement, I persisted in arguing a difficult business point, which was virtually unwinnable.

I never got the hang of the latter (to this day, I carry a shovel wherever I go), but I fully embraced the former principle. The gist of it is, in the absence of facts and figures, debates tend to be driven by (and remain unresolved due to) unfounded emotion rather than objective information.

Politics, especially these days, is the exception to this rule (facts don’t seem to matter anymore), but I’ve always found it useful in business and non-profit governance. I’ve kicked off many contentious strategy meetings with that adage (always with attribution, of course), and it seems to strike a chord with meeting participants — a kind of calming, stop-and-think moment before diving into the data.

Ed was always prepared with other handy maxims and metaphors as well as some home-spun philosophy befitting his North Carolina upbringing. “If you're gonna let the cat out of the bag, you better be prepared to deal with the cat,” he once admonished, when (mixed metaphor warning) I was about to open a can of worms with a radical new strategy proposal.

Ed’s aphorisms got people’s attention, lightened the mood, and often helped advance our discussions. He kept a great one in his hip pocket, yet, sadly, we never found occasion to use it over the 18 years I worked for him: “If you find a turtle on a fence post, you know it didn't get there by itself.” We’d glance at one another across a conference room table from time to time when an apt opportunity appeared to be emerging, but the circumstances were never quite right. It was my greatest disappointment in what you now know was a long line of jobs.

3) Activacation

Maybe I took things too far when I decided to apply Ed’s “information vacuum” principle to our extended family’s beach vacations. You see, I was repeatedly (and, of course, unfairly) accused of failing to participate in group activities.

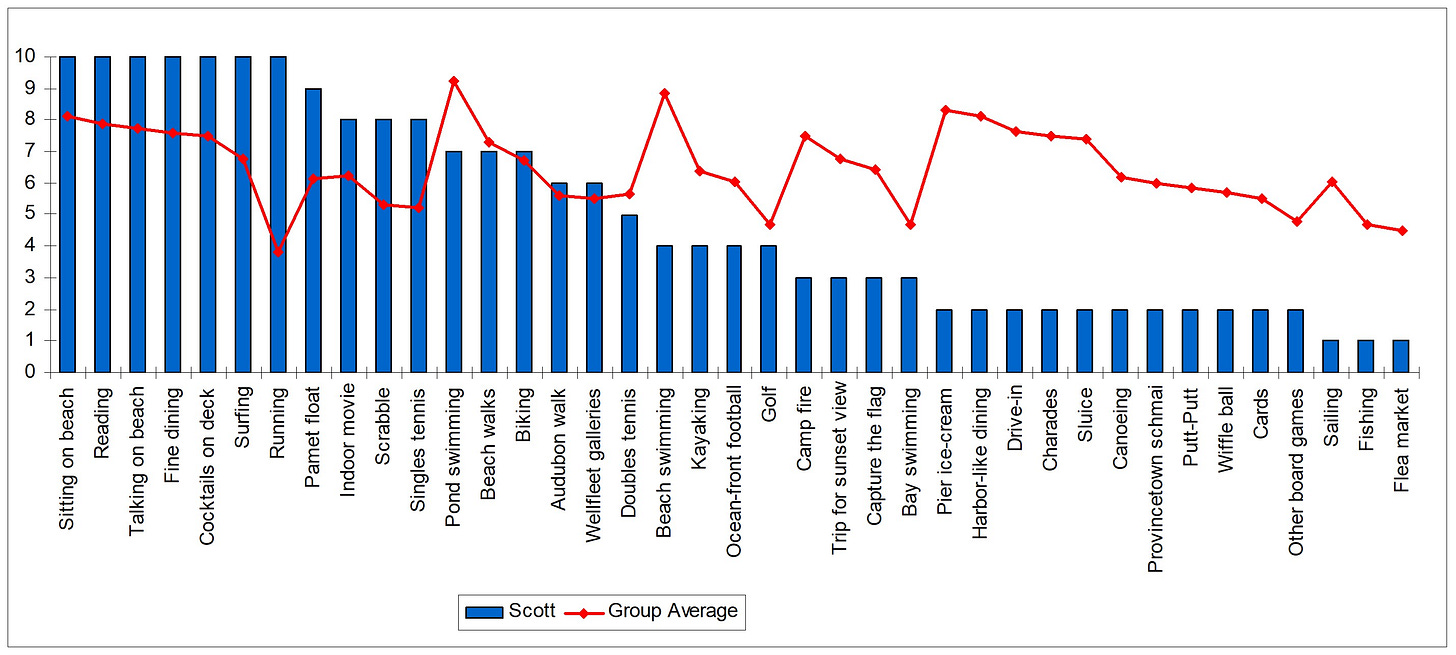

The argument dragged on for years, until I decided to counter the emotion with data. I asked each of our 17 family members to grade 39 activities on a scale of 1 to 10 — with 10 being the highest level of interest and 1 being the lowest.

Some relatives expressed concern for my mental health; they didn’t appreciate how quick and easy it is to enter data into Excel, push a few keys to create an array of charts and graphs, email the resulting 47-page deck to Kinkos, and have bound copies FedExed to the family.

Here are my own rankings (blue bars) relative to the group’s average rating by activity (red line):

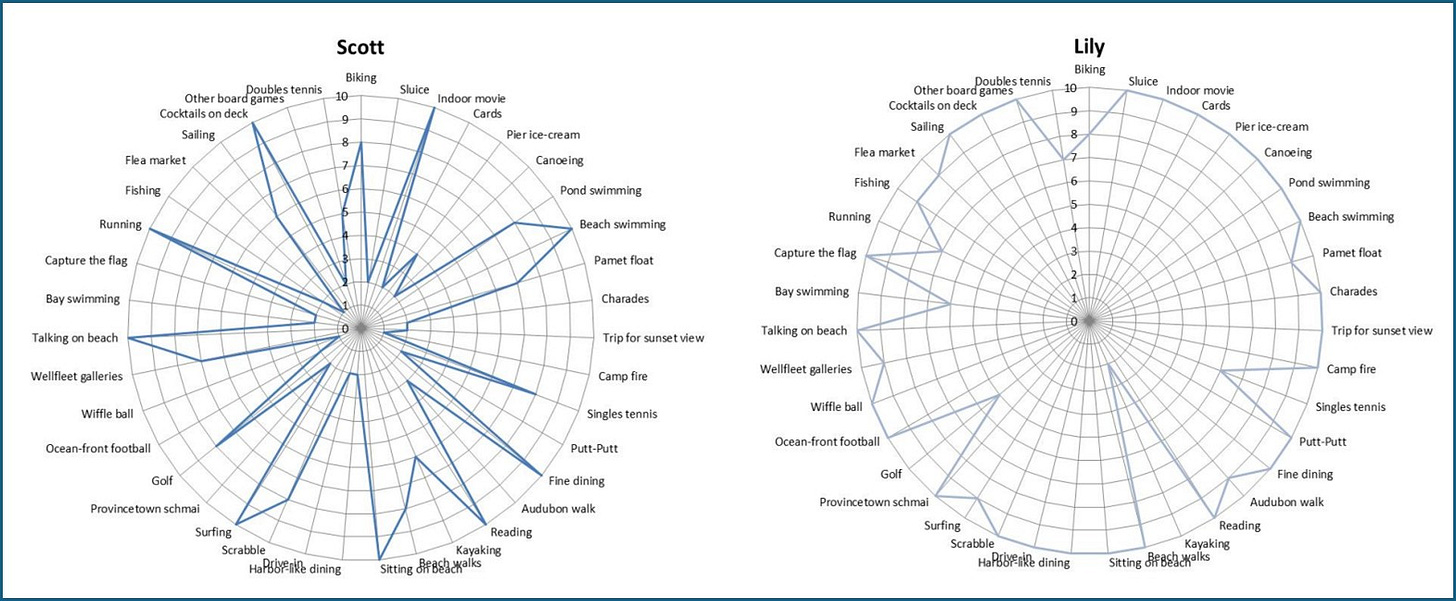

The data are irrefutable. They demonstrate that I do in fact engage in many activities but not necessarily those favored, on average, by the rest of the family. One major challenge, which no doubt warped the family’s perception of me, is that my relatives are hyperactive when it comes to sports, games, outings, and adventures. How can anyone hope to compete against people like my wonderful niece Lily (see the “spider charts” below), who loves any and all pastimes. I’m not indolent; Lily’s just gung ho about nearly everything.

In another case, I proved that a misalignment of interests had been causing a misperception of inactivity on my part. The chart below, for example, reflects an inarguable truth regarding the interests of another family member versus my own: He loves the drive-in; I hate it (too many mosquitoes). I surf, but he doesn’t (although now we both SUP). I love sitting on the beach and chatting; he gets a little antsy. He plays golf and sails; I don’t, but I bike and run. In other words, I’m quite active, just not in the ways he is. Q.E.D.

You’re no doubt wondering how this ended. Well, while many relatives found my data convincing (or so they said around page 18 of my presentation), nearly everyone claimed I needed help. “Once the simple task of entering the data is finished,” I pleaded, “all you have to do is click a button in Excel to generate a series of visuals.”4

The family suggested I take a vacation. “I’m already on vacation,” I pointed out. They proceeded to vote me off island.

Postscript: I conceived the title of this story, “Activacation,” as a portmanteau that combines the words “activities” and “vacation.” Before going to press (or whatever one does on Substack), I thought to Google the name, and wouldn’t you know it, there’s actually a game called ActiVacation®, developed during the pandemic by an Irish nurse named Ursula Kane Cafferty.

The aim of the game, according to its website, “is to get to the airport for a flight home before lockdown, after an activity-based vacation to every continent in the world.” You can see below that pony trekking and archery are among the choices.

It’s certainly not for me; I only ranked board games a 2 out 10 in the family activities survey.

2) Sidetracks

Palindrome of the Week: Doc, note, I dissent. A fast never prevents a fatness. I diet on cod.

Comment of the Week: A reader from West Hartford, CT responded as follows to my piece last week on the difference between pants, trousers, and slacks:

"Pants" is a funny word. "Trousers" is funny in a British accent. "Slacks" is not a funny word. See https://chavelaque.blogspot.com/2005/08/lines-from-star-wars-that-can-be.html.)

Principle of the Week: The Streisand Effect is “an unintended consequence of attempts to hide, remove, or censor information, where the effort instead increases public awareness of the information." The term was coined by Mike Masnick, editor of the Techdirt blog, after Barbra Streisand attempted in 2003 to suppress the publication of a photograph of her Malibu home. She sued for $50 million, claiming invasion of privacy. The lawsuit was dismissed. On pages 906 - 07 of her biography, My Name is Barbra, Streisand explains her position but concedes her lawsuit was a mistake. NB: I did not read My Name is Barbra! Her explanation is cited in the previous link.

Twisting and Turning: I recently learned that a meander is a decorative border in the ancient Greek tradition, featuring a continuous line of repeated motifs. The name is believed to have come from the winding path of the Maeander River in Asia Minor, now present-day Turkey.

Tough Times on the Heard and McDonald Islands: A BBC report, titled “How an island of penguins ended up on Trump tariff list,” explains.

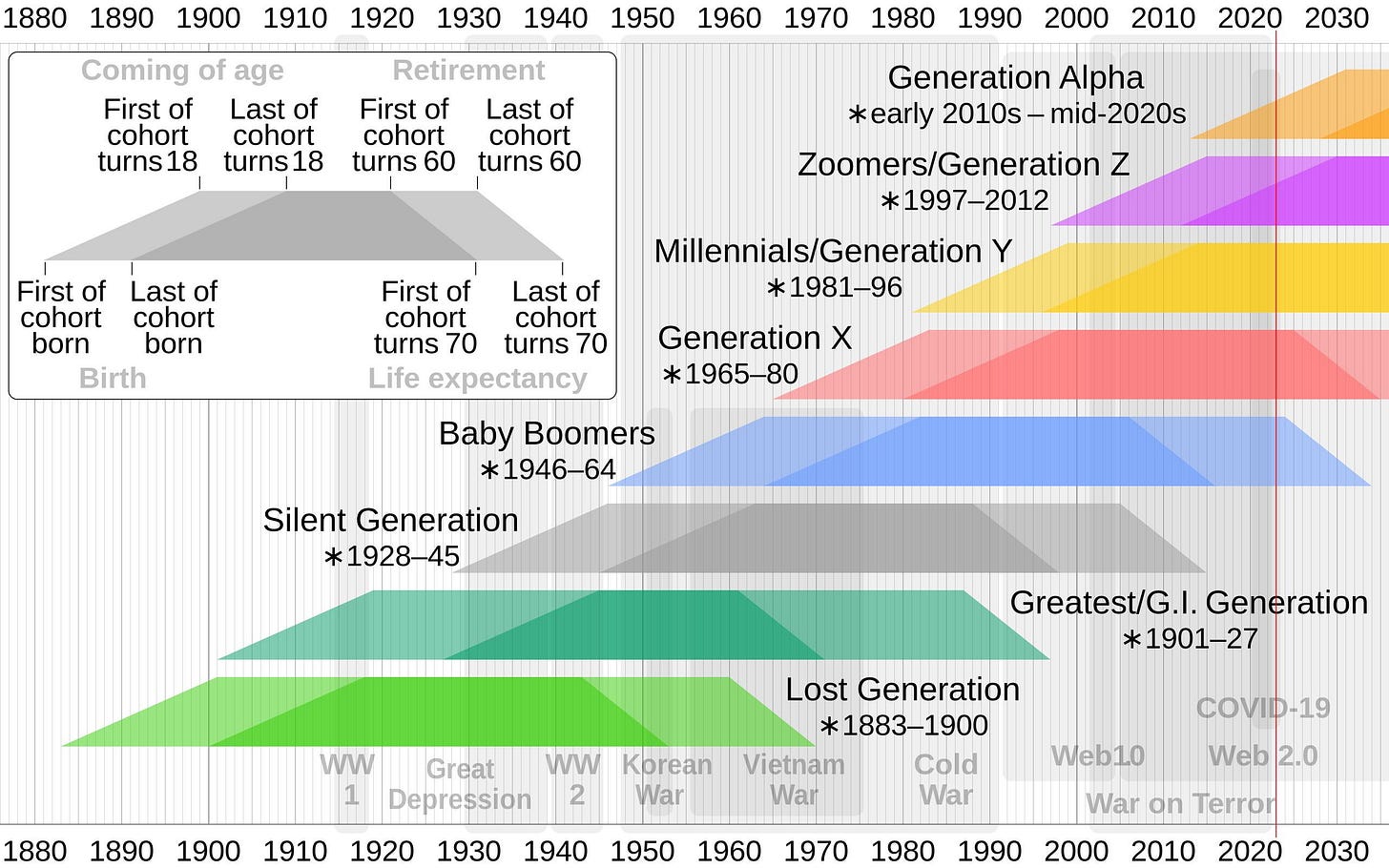

X, Y, and Z: For those of you, like me, who cannot remember the various generational definitions, here’s a helpful chart from the American Name Society, which promotes the study of onomastics:

1) Can You Please Use It in a Sentence?

The brilliant Matthew Yglesias, author of the data-driven

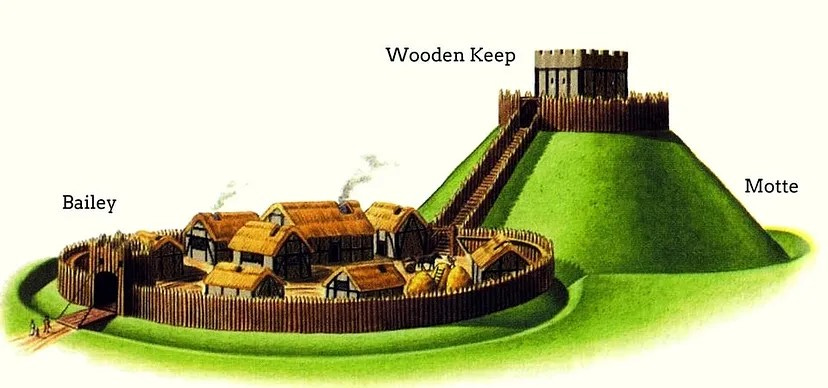

Substack, used a term I had never heard, in his Monday column: motte-and-bailey. Although the term sounds like a home good stores to me, it actually describes a type of a medieval castle fortification (the best known example is Windsor Castle), but it has come to describe a method of arguing — the Motte-and-Bailey Fallacy — “where an arguer conflates two positions that share similarities: one modest and easy to defend (the motte) [because it’s high ground] and one much more controversial and harder to defend (the bailey).”

The clearest example I could find was the following, from a website called QuillBot:

A politician asserts the urgent need for drastic measures to combat climate change, such as banning fossil fuels and implementing severe taxes on carbon emissions. When faced with criticism or skepticism about the economic feasibility or societal impact of such measures, the politician retreats to the safer position of advocating for incremental changes, such as improving energy efficiency and investing in green technologies. In this example of a motte-and-bailey fallacy, the extreme position (the bailey) advocates for sweeping changes to address climate change, while the moderate position (the motte) emphasizes more achievable and less controversial goals. This allows a person to shield a controversial stance from criticism and avoid defending it directly.

Will Motte-and-Bailey now become another example of the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon, which I wrote about last week — namely, a “cognitive bias in which a person notices a specific concept, word, or product more frequently after recently becoming aware of it.”

There’s a prize, by the way, of 20 wallet advice cards for the first reader who submits an example of a Motte-and-Bailey Fallacy in the comments section.

See Footnote 3 of last week’s column.

In The Dead Beat: Lost Souls, Lucky Stiffs, and the Perverse Pleasures of Obituaries, author Marilyn Johnson attributes “the comma” to the political consultant James Carville, but she acknowledges there is no general agreement on what to call “that phrase.” Others include “the who clause,” “the descriptive,” and “the tombstone.”

Always ready with a timely reference, Colin referred me to a recent Washington Post review of a new book by John Kenney, titled I See You’ve Called in Dead, in which the narrator is a depressed obituary writer. The reviewer, Ron Charles (one of my favorites), explains the premise, as follows:

One cold night, while circling the drain that’s become his life, Bud writes his own ludicrously spectacular obituary under the headline, “Bud Stanley, 44, former Mr. Universe, failed porn star, and mediocre obituary writer, is dead.” After noting that Mr. Stanley was killed in a hot-air balloon crash, he highlights his accomplishments as one of Gladys Knight’s original Pips, the first man to perform open-heart surgery on himself, the inventor of toothpaste and a member of the Jamaican bobsled team. It’s just a lark, a morbid way to get drunk on his own fermented despair. But then — oops — he accidentally publishes his little gag on the wire service, which sends the fake obituary to news organizations around the globe.

For the record, and in the interest of full disclosure, I did get some help with Excel from two exceptional (and exceptionally patient) colleagues in nearby offices. Despite the setbacks they suffered as a result of having to help me during business hours, they both have gone on to stellar careers at the top of their profession.

Revisiting… “One’s life summed up between two little dots with hanging tails,” someone wise recently wrote. Or five little dots if you were the Pope:

“Pope Francis, who rose from modest means in Argentina to become the first Jesuit and Latin American pontiff, who clashed bitterly with traditionalists in his push for a more inclusive Roman Catholic Church, and who spoke out tirelessly for migrants, the marginalized and the health of the planet, died on Monday at the Vatican’s Casa Santa Marta. He was 88.”

Sadly no mention of his crucial role in inventing fantasy College of Cardinals.

Sad news: (from the Times) "Wink Martindale, a radio personality who became a television star as a dapper and affable host of game shows like “Gambit” and “Tic-Tac-Dough” in the 1970s and ’80s and “Debt” in the ’90s, died on Tuesday in Rancho Mirage, Calif. He was 91."