Last week’s post, which dealt in part with retirement and mortality, prompted some readers to express concern that my audience consists exclusively of aging Baby Boomers. Not so. Although our data analytics team is on vacation, I can tell you that many of our subscribers have infants, young children, teenagers, and students in college.

This special child-rearing edition of Meandering Tour is for them — and for the Boomers who now have grandchildren. A few caveats:

I am not an expert in child development, although I roomed in graduate school with a candidate for a Master’s degree in education, who took a course in the field.

I also raised two children.

Some of the items below are serious, some lighthearted, but all true.

My apologies for writing way too long today. As they say, I didn’t have time to write short.

Most important: Do not try any of this at home. Oh, wait.

5) Alcohol and Drug Education

Many of you who have tweens or teenagers no doubt are concerned about their possible use of drugs and alcohol. We Boomers who raised kids once shared your fears, notwithstanding our own sins. That’s why, when my son was a teenager, I created the following infographic, which I left on our kitchen island for him and his friends to peruse. My purpose was serious, but I tried to take a humorous approach.

Often, when I came down to the kitchen in the morning for a cup of coffee, the “PowerPoint” (as it was first called) was defaced, often riddled with juvenile pictures of male genitalia. As my son’s friends emerged from slumber, demanding breakfast, they would often point at the sheet and laugh, “Hey, that’s funny, Mr. Sherman.”

“Please, call me, Scott,” I’d say, thereby relinquishing whatever meager authority I might have had. They especially ridiculed my use — twice! — of the word “albeit” in the lower right-hand corner. Fair enough. Still, I’d try to reason and cajole and engage.

I would simply print a fresh copy for the following weekend. But as the defilement continued, I decided to save paper by laminating a copy. This tactic worked as an art preservation technique, but I was concerned that the “Laminate” (as it was later renamed) might not achieve its intended purpose.

When the gang went off to college, I made Laminates for them. A few actually posted them in their dorm rooms and sent me photos (see below). They were joking around, of course, but I found the gesture heartwarming — and tenuously suggestive of the possibility of some positive effects, albeit over the long term.

Still, I hope the resulting funny conversations at the time, and to this day, actually achieved something — perhaps improved communication, a meaningful connection, an appreciation of adult concern?

Give it a try — in Laminate form or some other medium. You’re welcome.

4) College Counseling

Some subscribers have high school seniors who are about to hear from college admissions offices. I remember how tense this time can be.

When the dust settles, your child has decided where to go to school, and you start getting a little teary, you’ll need to pull yourself together and provide some advice, even if your scholar pretends not to be listening.

I decided to try something that might survive the trials and tribulations of university life: a wallet card. Here’s what I gave to my son when he graduated from high school in 2014. Are you sensing a pattern in my behavior?

As you might imagine, you can’t just order one of these. At the time, I think I had to purchase 250 cards, albeit at a not unreasonable price.

The stockpile lasted for years. I gave some to my son’s high school friends. I’d jam them into my son’s luggage every time he’d head back to college from vacation. I’d put them in hiding spots in his dorm room over Parents Weekend, and gave them to roommates. I even slipped one into the shirt pocket of a dozing sophomore at a pre-game tailgate study group.

To this day, some of my son’s friends pull the cards out of their wallets to show me. Occasionally, someone will ask for a replacement if they’ve lost it.

I was inspired to make the cards by my sister-in-law Suzie who, in 2004, gave the following list (one copy only) to her daughter when she left for college.

These were simpler times.

3) Face Time

In January 2024, I became a grandfather. Watching Charlotte, now 14 months old, grow has been enchanting and endlessly fascinating. At my own age of 828 months, I found it remarkable to see her react to my voice and facial expressions as well as begin to navigate the physical world. I’ve been moved watching my daughter, son-in-law, and so many members of our large, extended family joyfully interact with her.

These endless exchanges surely have a positive impact, right? Over the long term, not just in infancy, yes? And what about the countless children deprived of such encounters on a regular basis, or subjected to inconsistent engagement by adults who ricochet between smiling and other facial expressions that convey sadness or displeasure? Surely, babies treated more positively will fare better?

It turns out the (research-based) answer is, yes. A few years ago, I had the good fortune to meet Dr. Barry Zuckerman, Professor and Chair Emeritus of the Department of Pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine, who has shared with me some of the discoveries and innovations in behavioral pediatrics. One is the so-called “Still Face Experiment,” conducted by Dr. Edward Tronick.1

The following is a description of the experiment from Psychology Today, and here’s a video demonstration, featuring Dr. Tronick himself.

The baby is in a seat facing her mother and the mother is talking, smiling, and making eye contact, and the infant responds by vocalizing, smiling back, and pointing at things in the room. At one point, the mother turns away and when she faces the baby, what the infant sees is a still, unsmiling face. The baby goes into overdrive to reengage her or his mother—doing all the things that previously have garnered attention — but no go; the mother’s face remains still. What you see on the video is heartbreaking: When the infant realizes that while Mommy is there, she is also somehow gone, the baby begins to melt down. She looks away, she waves her arms in protest, slumps in the seat, and then begins to wail. It’s at that point that the mother relaxes her face and starts interacting with the infant again, re-establishing and repairing the connection. It’s worth noting that the baby is relatively wary and that it takes a bit of time for her to recover.

Among the findings and implications of the experiment, reportedly one of the most replicated in the field of developmental psychology, are the following points, quoted from a variety of sources — some the lay press, others peer-reviewed journals.

“Attunement and interaction are essential to the infant’s thriving and development during the first three years of life and have effects that reach way beyond those years and into adulthood.”2

“The normal feedback infants receive from their mothers in face-to-face interaction was distorted by having the mothers face their infants but remain facially unresponsive. The infants studied reacted with intense wariness and eventual withdrawal, demonstrating the importance of interactional reciprocity and the ability of infants to regulate their emotional displays.”3

“[E]xperiments with toddlers—light-years ahead in terms of development and already talking—quelled any doubts. The toddlers acted precisely the way the infants had but with more intensity; they worked hard at trying to reengage their mothers by using speech. They raised their voices in response to the still face, waved objects in front of her, and tugged at her to try to get her to respond. The toddlers exhibited the same behaviors as the infant cohort: a pattern of protest, followed by a flood of emotion, and then turning away so as not to experience more emotional pain. Once again, repairing the connection took time.”4

“When maternal attunement is absent on a regular basis or inconsistent, the child’s mental models of how relationships work and whether people can be trusted to be there for you shift toward the negative. These mental models become what are called adult attachment styles (secure, and the three styles of insecure attachment: anxious-avoidant, dismissive-avoidant, and fearful-avoidant). The insecure styles of attachment emerge when maternal attunement is sporadic or non-existent.”5

“Show your child respect and understanding in moments when they feel misunderstood, upset, or frustrated. Validate their emotions and guide them with trust and affection. Your child’s mastery of understanding and regulating their emotions will help them to succeed in life.”6

“The third segment [of the experiment] illustrates the ‘repair’ of the mismatch, which can take some time until the infant can calm down and smile back, indicating full re-engagement and return of physiologic homeostasis. With the experience of repairs, the infant gains a sense of trust in the mother and a feeling of mastery that leads to resilience in face of future stress.”7

“However, at the extreme, a mother’s lack of responsiveness and failure to repair over too long a period of time, which occurs disproportionately among mothers with mental health problems, drug addiction, and stresses related to poverty, likely exceeds an infant’s behavioral and neurophysiological capacity to cope, as seen in neglected children. Such stress is toxic and leads to relational difficulties and developmental derailment….”8

So, yes, positive face time with our babies will pay off. It’s heartbreaking, however, to think about infants who do not receive the same consistent attention and affection, not only due to parental missteps (we all make mistakes, get tired, etc.) but, more broadly and impactfully, due to challenging life circumstances so many parents have to struggle with, through no fault of their own.

Dr. Zuckerman has thought about it — and done something. He co-developed an app for pediatric primary care called Small Moments, Big Impact to “promote the mother-infant relationship and emotional well-being for low-income mothers from birth through the first six months of their baby's life.”9

2) Sidetracks

Question: Why do grandchildren and grandparents get along so well. Answer: Because they have a common enemy. (t/h Glenn M)

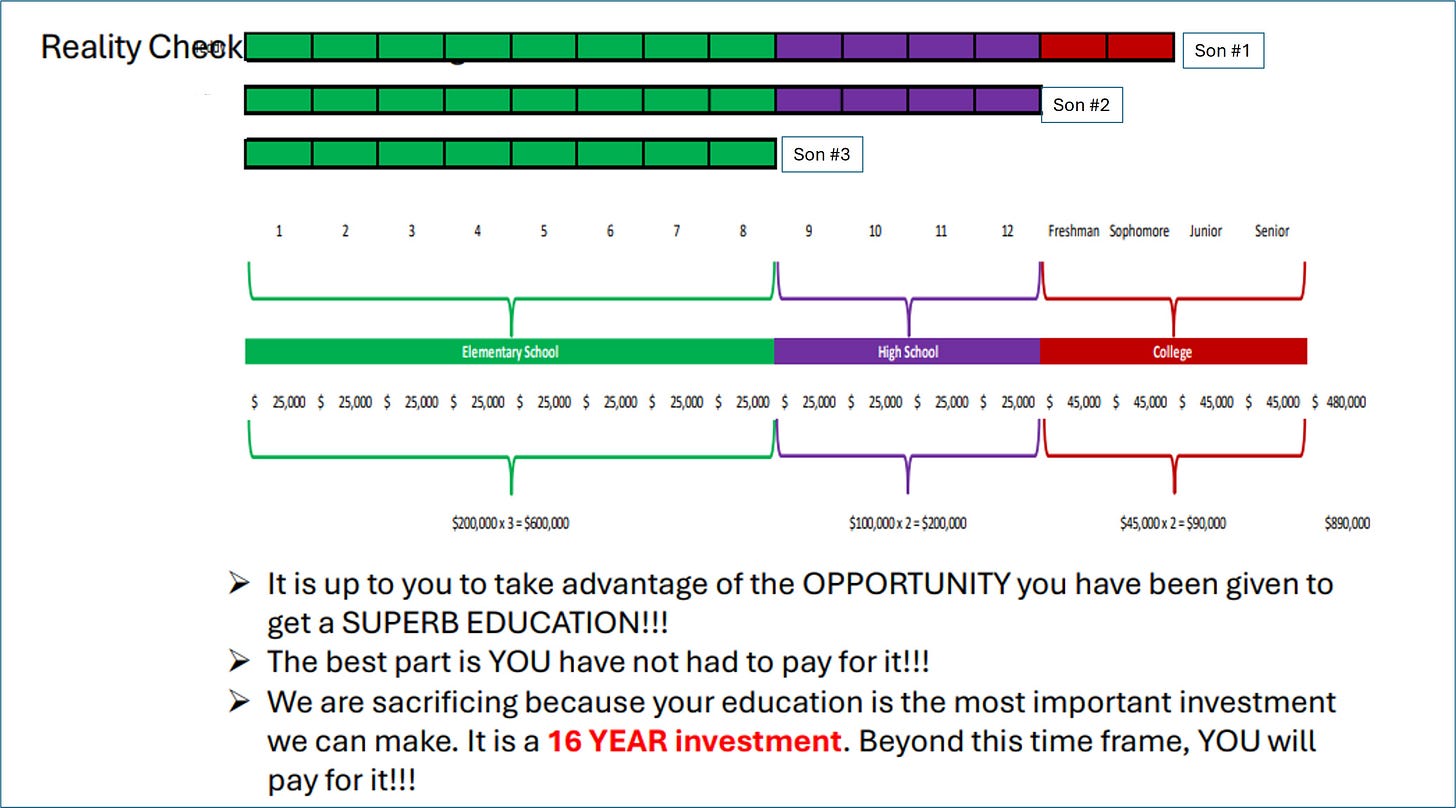

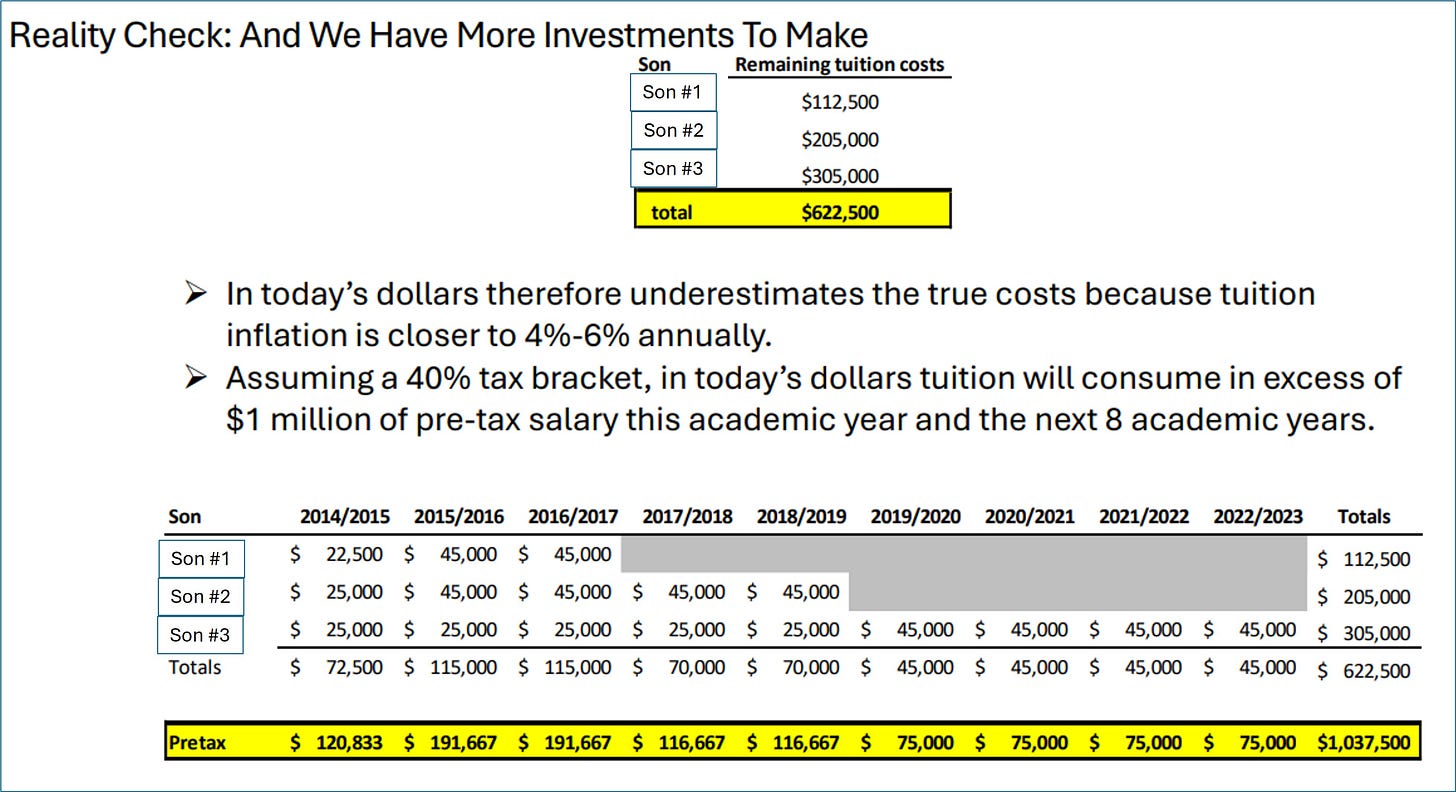

Family Dinner: I’m not the only one who’s used multimedia for child-rearing purposes. My friend Tedd, who has three grown sons, used to give PowerPoint presentations at dinner about subjects such as character, integrity, education, and financial matters, among other subjects. When his sons were in high school, he gave a meal-time disquisition about the total estimated cost of their private school and college education, and his expectation that after 16 years of funding, they would have to pay to support themselves. Below are two of the slides from that now-famous TEDD Talk, including this rather pointed bullet point: “We are sacrificing because your education is the most important investment we can make. It is a 16 YEAR investment. Beyond this time frame, YOU will pay for it!!!” Tedd reports that all three sons have graduated from college, two are gainfully employed, and the third is in his first year of business school where, as required, he is off the family plan. Well done — the child-rearing, not the roast beef.

Baby Names: The Economist just published a feature, analyzing the first names of the nearly 400 million people born in the U.S. and Britain in the past 143 years. There may be a paywall, but if not, click through the various charts and graphs to get a sense of the power of big data analysis, search historical databases for trends, and maybe name your next child. Among the findings:

Based on the connotations of popular names, the magazine found that names associated with beauty have become more popular of late. “If beauty is desired in girls, brawn has muscled into male names: 70% of boys in America and 55% of boys in Britain have a name that evokes powerfulness. (The most popular boys’ names in America, Liam and Noah, are associated with strength.)”

In the U.S., no first name has come close to measuring up to the “Linda boom of 1947” — 100,000 girls that year. In 2023, only 414 children were named Donald. The name Taylor for girls has slumped as well, “perhaps because parents fear their children will feel eclipsed by the star.”

In 2023, Muhammad was the most popular name for boys in England and Wales (4,600, or 1.7%, of infant boys).

Infant Memories: According to a new report in Science based on neuroimaging, the hippocampus (a brain region important for memory) constructs short-lived memories when we’re around one year old. This runs counter to Freud’s theory of “infantile amnesia,” which has prevailed for more than a century. “The findings indicate that memories [about people, places, and things] can indeed be encoded in our brains in our first years of life,” according to an account of the study in Science Daily. The research suggests that the fleeting nature of babies’ memories is due to the “immaturity of post-encoding processes, such as memory consolidation or retrieval.” So, until we know more, just smile and coo and don’t mention your Dashlane password in front of Baby Theodore.

1) Nature vs. Nurture

I bet you’re thinking (at this point, probably desperately hoping) that I can’t go back any further than the fleeting memories of a one-year old to explore what makes us who we are. Well, I can’t, but some researchers think they can, according to recent articles in the field of epigenetics, the study of how our environment influences our genes. If they’re right, “nature” will gain some ground on “nurture.”

Let’s start by recalling an item from last week’s post — namely, Seligman’s PERMA strategy for wellbeing, which concedes that the ability to experience positive emotion is partly heritable. In other words, “Some people are, by disposition, low in the extent to which they experience positive emotion.”

So, what else in our DNA might predispose us to certain behaviors, and how far back do such encoded influences go?

Last month, researchers published a paper in Scientific Reports titled “Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees.” A summary account of the study in Science suggests that “traumatic experiences—such as witnessing violence or being a victim of it—affect more than just those who live through them. The impacts can echo through generations, subtly influencing how survivors’ descendants react to situations even if they were never exposed to the original conflict.” The Scientific Reports abstract concludes, “This is the first report of an intergenerational epigenetic signature of violence, which has important implications for understanding the inheritance of trauma.”

Last year, The Guardian also reported on the possibility of inheriting ancestral trauma: “Scientists working in the emerging field of epigenetics have discovered the mechanism that allows lived experience and acquired knowledge to be passed on within one generation, by altering the shape of a particular gene. This means that an individual’s life experience doesn’t die with them but endures in genetic form. The impact of the starvation your Dutch grandmother suffered during the second world war, for example, or the trauma inflicted on your grandfather when he fled his home as a refugee, might go on to shape your parents’ brains, their behaviours, and eventually yours.”

And just last week, The New York Times ran an essay about the emerging field of sociogenomics, a “fusion of behavioral science and genetics.” “The part of this research that really blows me away,” writes the columnist, Dalton Conley, author of The Social Genome: The New Science of Nature and Nurture,

is the realization that our environment is, in part, made up of the genes of the people around us. Our friends’, our partners’, even our peers’ genes all influence us. Preliminary research that I was involved in suggests that your spouse’s genes influence your likelihood of depression almost a third as much as your own genes do. Meanwhile, research I helped conduct shows that the presence of a few genetically predisposed smokers in a high school appears to cause smoking rates to spike for an entire grade — even among those students who didn’t personally know those nicotine-prone classmates — spreading like a genetically sparked wildfire through the social network.

Okay, I’m done. I’ve stuffed every relevant thing I’ve recently read into this special child-rearing edition of Meandering Tour. I’m intrigued, as I hope you are. I also put many of these breakthroughs in the category of “best of times,” not “worst of times.” The promise of such research is extraordinary.

But for now, until there are more definitive findings, I suggest we just refer to Ye Olde Wallet Card. It seems sensible on its face (although I realize I’m biased), and I suspect that much of it is actually supported by science.

0) Loose Ends

Special Mention: In last week’s post, I wrote at the end of footnote 1, “If anyone is reading this footnote, please raise your hand in the comments section, and you’ll get a special mention in next week’s column.” Ten out of more than 600 readers mentioned the footnote. They were (in alphabetical order): Dan O, Darrell B, Doug K, Eddie L, Glenn M, Jeff W, John C, Mallory M, Nancy L, and Tony T.

Nancy L wins the prize for the best comment: “Great post. Footnotes are magic.”

Jeff W takes second place for merely reading that far.

About Your Comments: Many readers wrote last week about a variety of subjects in addition to footnotes. Please know that I read and respond to each and every comment, but it appears that Substack does not notify you when I do so. (I’m looking into this.) So, if you write a comment, please check back to see what I’ve said in response.

More Citations: Below are the footnotes to today’s post. They’re “magic.”

Note: I haven’t written formal footnote citations in years. If you see any mistakes, please let me know in the comments section (along with suggested corrections), and you’ll win a free subscription to Meandering Tour (oh, wait) plus (to the first helpful responder) a stack of college advice wallet cards (shipping and handling included). If you do not want the cards, please let me know, and I’ll offer them to the next vigilant commenter.

Tronick, E., Als, H., Adamson, L., Wise, S., and Brazelton, T., "The Infant's Response to Entrapment between Contradictory Messages in Face-to-face Interaction," Pediatrics, September 1978, Vol. 17(1), pp. 1-13,

Streep, P., “Why the ‘Still-Face’ Experiment Was a Game-Changer, Psychology Today, July 10, 2023.

Tronick, et al., supra note 1.

Streep, supra, note 2.

Id.

The Gottman Institute, https://www.gottman.com/blog/research-still-face-experiment.

Zuckerman and Tronick, “The Still-Face Paradigm: Training Model for Relational Health,” Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 44, No. 2, February/March 2023.

Id.

See also this webinar on the “Small Moments, Big Impact” project:

Scott!!! Oh my goodness how lucky I feel to have found your Substack. My oldest son is heading to college in a few short months so I’ve already sent your words of wisdom to him with a particular highlight on items #8 and the bonus suggestion. 💕. What a fascinating idea to send our kids out into the world with a handy reference card in case they forget any of the sage parenting advice they were surely listening to we’ve been doling out for the last 18 years. My husband and I may need to steal this concept from you - imitation is the finest form of flattery, right?

BTW, I was trying to explain to my son and husband how I knew you and how much I learned from you in a short amount of time at TRP and why they should listen to your advice and it brought back good memories. You really inspired me a ton and I consider myself lucky to have had the opportunity to see you in action wheeling and dealing doing what you do best - spinning stories and closing deals. I hope retirement is treating you well and keep writing! Best, Susan Foster-Garner

Excellent advice and analysis, Scott. How I wish my kids had the benefit of a father like you. Luckily, they had my Dad, who imparted similar wisdom. My son is following my life rules well, but a laminated wallet card would be a blessing.