Meandering Tour

Nominative Determinism | Digital Distractions | Ancient Rome | Tok Pisin | Graham Crackers

Greetings from the tour. For those of you who have joined me today via social media links, please consider subscribing directly for free weekly delivery to your e-mail address. Based on Substack analytics, I estimate that we’ve been averaging about 700 - 800 readers a week, but the official count would be more accurate, and maybe much higher, if you would access Meandering Tour by clicking here. I’d appreciate it. Thanks very much.

5) What’s in a Name?

Last weekend, after her precocious four-year-old attended the latest Very Young People's Concert at the New York Philharmonic, my niece — knowing of my interest in nominative determinism — sent me the program.

You’ll notice that the Very Young People’s Concert was hosted by Rebecca Young, who joined the Philharmonic in 1986 as its youngest member. She is now the orchestra’s associate principal violist.

“What’s in a name?” Juliet asks Romeo in Act 2, Scene 2, suggesting it’s just a label, with no intrinsic value.

Nominative determinists beg to differ; they believe people gravitate towards work that fits their names. Think: sprinter Usain Bolt, poet William Wordsworth, poker player Chris Moneymaker, psychiatrist Jules Angst.

Academicians actually study this phenomenon, sometimes referred to as an “aptonym.” There’s a scholarly publication called NAMES: A Journal of Onomastics. Onomastics is the study of the origin and history of proper names, not something prohibited by the Old Testament.

Recent articles, I kid you not, include:

“Examining the Association Between Name Characteristics and Academic Career Success of UK Neurologists”

“For the Love of Karen: A Socio-Onomastic Investigation into Prejudice and Discrimination Targeting Karen and its Name-Bearers”

“What's in a Tibetan name? Toponymic Opacity along the Bird River in Sanjiangyuan National Park, China”

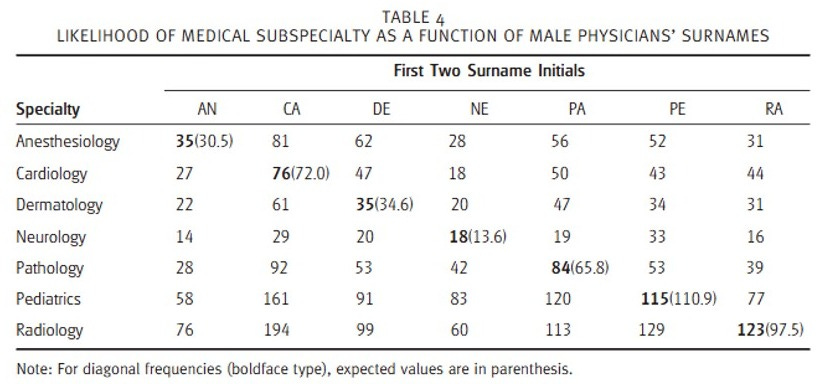

How about this one from 2010: “Influence of Names on Career Choices in Medicine.” I can’t do it justice without quoting the abstract in full:

Three studies showed that medical doctors and lawyers were disproportionately more likely to have surnames that resembled their professions. A fourth study showed that, for doctors, this influence extended to the type of medicine they practiced. Study 1 found that people with the surname “Doctor” were more likely to be doctors than lawyers, whereas those with the surname “Lawyer” were more likely to be lawyers. Studies 2 and 3 broadened this finding by comparing doctors and lawyers whose first or last names began with three-letter combinations representative of their professions, for example, “doc,” “law,” and likewise found a significant relationship between name and profession. Study 4 found that the initial letters of physicians’ last names were significantly related to their subspecialty, for example, Raymonds were more likely to be radiologists than dermatologists. These results provide further evidence names influence medical career choices.

Table 4 will elucidate the latter point.

NAMES must have had a shortage of submissions for its first quarterly issue this year. What else could explain the inclusion of the review of a recent book called “A Teacher’s Guide to Learning Student Names: Why You Should, Why It’s Hard, How You Can.”

4) Tech Temptation

In 2013, when I was visiting colleges with my son, we received permission to attend a class called “The American Novel Since 1945,” taught by Amy Hungerford, then at Yale, now at Columbia. The assignment that day was “Girl with Curious Hair,” a short story by the late David Foster Wallace. (“Short” in this case meant 35 pages. Has anyone you know ever finished reading Wallace’s 1,100-page novel Infinite Jest?)

I read the challenging story in advance, so I could fully appreciate the insights of one of the finest lecturers on contemporary literature. My son and I took seats in the back row, as about 50 students filed into the classroom and opened their laptops.

As I hung on Dr. Hungerford’s every word, I gradually noticed that some of the students were gazing at their computer screens, with one in particular typing away on Facebook. I wondered in that moment if I could ever go back to school under these conditions, distractable and digitally addicted as I was even then, 12 years ago. Of course, it’s gotten much worse since, with the ubiquitous use of powerful mobile phones. Many scholarly publications have demonstrated that the Internet has literally (correct use of the term here) rewired our brains.

I had an opportunity to test myself two years ago when I audited an undergraduate seminar on the history of human genetics at Johns Hopkins University. I found the class riveting, thanks to the subject mastery and storytelling of the professor and the intellectual engagement of the students.

Still, with my laptop open to the reading materials and my iPhone balanced next to it on my old-fashioned writing tablet chair, I struggled mightily during the three-hour classes not to check my e-mail or the perpetually breaking news. Overcoming the compulsion took great effort. At the midway break, I immediately opened my phone, soothed by the resulting rush of dopamine.

My tech addiction dates back to the late 1990s when my employer gave me my first Blackberry — the gateway device. It was a marvel; I couldn’t be without it, even though coverage was spotty in those days, especially when I went on vacation to Cape Cod National Seashore. There, at our small cottage, I found a single spot, right outside the screen door, with reasonably reliable Internet reception. Because it was in direct sunlight, however, I created what came to be known as the Blackberry Cabana, which happened to be located just over a mile north of Marconi Station, the site of the first transatlantic wireless communication between the U.S. and Europe, in 1903.

Where does this leave the younger generation, the so-called “digital natives” who’ve already spent their entire lives glued to their devices? Many experts have studied this challenge and prescribed solutions such as banning mobile phones in primary and secondary schools — most recently, Jonathan Haidt in The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

My peers and I had the opportunity to develop “normal” neural pathways before our later-in-life addictions started to alter our synapses. We at least can recognize the reprogramming we’ve undergone and perhaps take steps to stem the tide.

By coincidence, this very morning, I had just finished walking the beach on Cape Cod, when I read the following excerpt from a 2012 New York Times op-ed sent to me by a subscriber concerned about technology’s erosion of interpersonal relationships:

I spend the summers at a cottage on Cape Cod, and for decades I walked the same dunes that Thoreau once walked. Not too long ago, people walked with their heads up, looking at the water, the sky, the sand and at one another, talking. Now they often walk with their heads down, typing. Even when they are with friends, partners, children, everyone is on their own devices.

True enough; I’m guilty myself. Not this morning, though, as I was walking with my dogs Luna and Adley, to whom I always give my undivided attention.

3) Veni, Vidi, Minxi

Now I Know, a newsletter with roughly 99,000 more subscribers than Meandering Tour, offers a daily feed of unusual and amusing stories. (I’ve learned that these publications are sometimes referred to as “serendipity engines” to reflect the fascinating, yet random, information they serve up.) On Monday, NIK published an article titled “The Ancient Roman Pee Tax,“ based on a paper in the American Urological Association’s Journal of Urology, about the collection, distribution, and taxation of urine in the Roman Empire.

Urine, the researchers report, was then a valuable commodity, used as a raw material in tanning, laundering, and, uhm, toothpaste. Wealthy buyers of the excrement paid a special tax (vectigal urinae) levied originally by Emperor Nero and later reinstated by Emperor Vespasian in 70 CE. According to the journal article,

Lower classes of the empire would collect their urine and empty it into cesspools. Added to this was the effluent from public lavatories. The tax applied to all public toilets within Rome's now famous Cloaca Maxima (great sewer) system and funded their further development. The urine . . . was used in the tanning industry, where it was mixed with the hide to soften it, loosen the hairs and dissolve the fat from its surface. It was also used as bleach where tunics were immersed in urine and whitened. The smell of urine was then washed out with water. Wealthy Romans, especially women were willing to pay large sums of money for toothpaste in which urine was the key ingredient. It was thought that one's own urine or that of another Roman would not be effective but rather Portuguese urine provided an ideal whitening effect. Thus, large quantities of the “stronger” Portuguese urine were imported for this purpose.

"Vide, Mamma, nullae cavitates!"

I’ll let Dan Lewis (the founder and writer of Now I Know as well as a “recovering lawyer” like me) pick up the public health and military history from here:

In the 1800s, France introduced public urinals . . . which were in use until the 1960s. Italy had something similar at around the same time. The French word for these structures is “vespasienne” and the Italian term is “vespasiano,” both of which are named after the Roman emperor [see above] who decided to tax pee. . . . The vespasiennes of Paris may have helped the French resist Nazis during World War II. As the Guardian notes, Germans were unfamiliar with the public urinals and disgusted by them, avoiding the installations whenever possible. The French used that to their advantage. Per the Guardian, the urinals “served as important meeting places for résistants to exchange information on enemy troop movements.”

Your analysis?

2) Sidetracks

Email Bankruptcy: One of my favorite concepts is email bankruptcy, although I’ve never had the nerve to do it myself nor do I know anyone who has. For readers who haven’t heard of the practice, here’s how it works: You have so many emails in your inbox that you 1) simply delete them all in one fell swoop, then 2) send a single bcc message to your entire contact list, saying you have deleted all your emails, so if anyone is waiting for a response, they should resend their email. The next best thing may be in the offing. At SXSW London last week, Sir Demis Hassabis, founder of Google’s AI platform, DeepMind, said his team is working on an AI-powered email assistant that could help sort through and reply to messages. “The thing I really want — and we're working on — is can we have a next-generation email,” Hassabis said. “I would love to get rid of my email. I would pay thousands of dollars per month to get rid of that.” Last year, Sir Demis shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his use of artificial intelligence to predict protein structures. He developed and used something called AlphaFold2, the accuracy of which “has been evaluated against experimentally determined protein structures using metrics such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD),” the measure of the average distance between atoms. All very well and good, but he hasn’t a clue what he’s up against in my inbox.

Gone crackers: I was enjoying some Graham Crackers after dinner last week and all of a sudden wondered how and where they originated. A few days later, this item popped up in one of those “serendipity engines” I mentioned: “Inside The Strange Origins Of Graham Crackers And Why They Were Invented.” In short, they were developed in the mid-19th century by Sylvester Graham, an advocate of the temperance movement, who hoped that the snack would help curb Americans' sexual desires and other pleasures. Remember that the next time you eat a S’More.

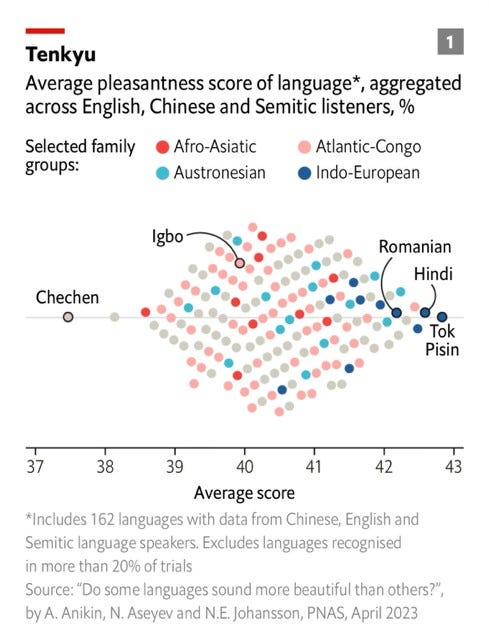

Ejectives, Diphthongs, and Nasal Vowels: The Economist reported that three scholars ranked the sound of 228 worldwide languages on a “pleasantness” scale, from ugliest to most beautiful. (Who’s asking?) The researchers recruited 820 people from three different language groups — Chinese, English and Semitic (Arabic, Hebrew and Maltese speakers) — to listen to the same movie clip in various tongues and rate the attractiveness of the languages. According to The Economist’s account of the study, published in the esteemed Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS),

On a scale of 1 to 100, all fell between 37 and 43, and most in a bulge between 39 and 42 [see chart below]. The highest-rated? Despite the supposed allure (at least among Anglophones) of French and Italian, it was Tok Pisin, an English creole spoken in Papua New Guinea [click here to listen to a sample]. The lowest? Chechen. The three language groups broadly coincided in their preferences. But the differences between the best and worst-rated languages were so slight—and the variation among individual raters so great—that no one should be tempted to crown Tok Pisin the world’s prettiest language with any authority.

1) Reader Mail (Local, National, and International)

Kathy from Maine sent this excellent cartoon in response to last week’s “apostrophobia” post, in which I expressed frustration over the continuing misuse and overuse of apostrophes.

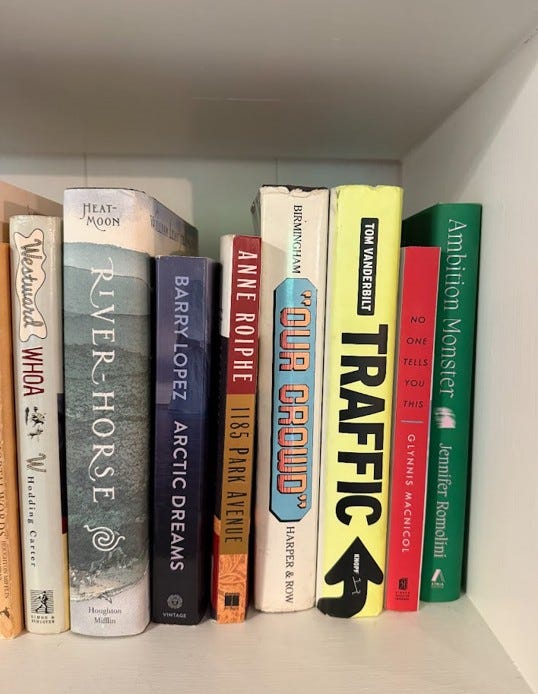

Abby from Vermont and Ted from Mexico both responded to my recent article about jaywalking to say they own copies of one of the sources I cited: a book called Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do. Abby sent me a picture of her bookshelf to prove it. She says she read some of it but quickly pulled over.

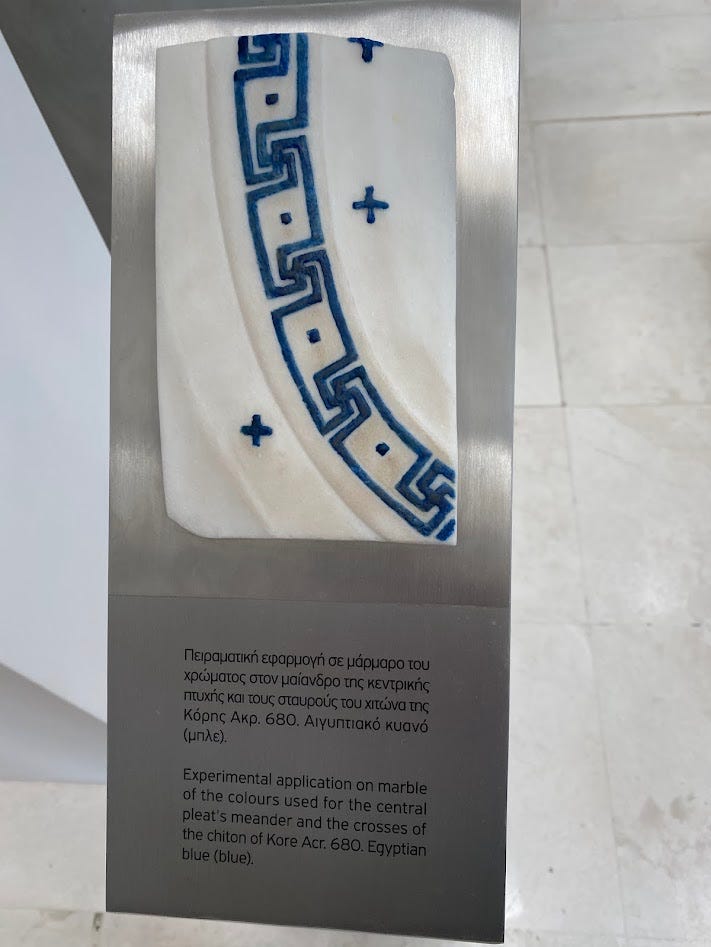

Darrell wrote from Athens, Greece to share this photo of a “meander” in the Acropolis Museum. As I wrote a few months ago, a meander is a decorative border in the ancient Greek tradition, featuring a continuous line of repeated motifs. The term is believed to have come from the winding path of the Maeander River in Asia Minor, now present-day Turkey.

Steve from Maryland lamented the significant decline in the use of semicolons, according to a recent study reported by The Guardian. Usage in British books has dropped by nearly half, from one in every 205 words in 2000 to one use in every 390 words today. The research also found that 67% of British students never or rarely use the semicolon; just 11% describe themselves as frequent users.

Others wrote to say they approve of em dashes (the subject of a story last week) and use them frequently — they just didn’t know they are called that.

Thanks, everyone, for reading so closely and joining me in the appreciation of language, grammar, and punctuation as well as arts, culture, and technology — with, I hope you agree, a touch of humor.

Your column Scott makes me wonder why one of my classmates in medical school, Brenda Nurse, chose her profession.

I read (and finished) Infinite Jest during a six or seventh month stint where I was selling mattresses. Truly, being able to lounge on a bed all day getting paid to read a doorstop is the best way to experience such a hefty, complex tome.