5) Retirement Plan

At my age (third age? young-old? perennial?), I have many friends and acquaintances who are considering retirement or, like me, have already taken the plunge.

Folks often want to talk about whether they should retire, what retirement is like, the key to a successful retirement, and so on. The only advice I have is this: when two or more retirees get together and the subject invariably turns to health, each person should be limited to discussing only one organ. (Organ recitals, if you will.) An anatomical structure (e.g., spine) or biological system (e.g., respiratory, digestive) counts.

Other than that, just live your life, I say. Advice columns and how-to books, on any subject, always seem too pat. We’re all a product of our own experience, so one size never fits all.

That said, I always find that a framework for analysis rather than specific instructions can be helpful. My friend Carl, a psychotherapist who is still working full-time, recently told me about a 13-minute TED Talk, titled “The 4 phases of retirement,” watched by 3.2 million viewers since it first aired less than three years ago. The speaker, a former financial advisor and educator named Riley Moynes, doesn’t so much preach about how to have a fulfilling retirement (which, given increasing longevity, could account for a third of one’s life span) as provide a roadmap for what to expect in retirement — psychologically, not financially.

And for this reason, his model, albeit based on a series of interviews, not formal research, has something for all of us to consider, in my opinion.

Phase one, Moynes says, is the “vacation phase, and that’s just what it’s like. You wake up when you want, you do what you want all day, and the best part is that there is no set routine. For most people, phase one represents their view of an ideal retirement, relaxing, fun in the sun, freedom....”

Phase two is “when we feel loss, and we feel lost” as retirees realize they lack, to one degree or another, the routine, identity, work relationships, purpose, and, in some cases, power they had valued at work.

Most people find a way to get to phase three (again, Moynes does not explain how to), which he calls “trial and error.” In this phase, “we ask ourselves, how can I make my life meaningful again? How can I contribute? The answer, often, is to do things that you love to do and do really well. … [I]t’s really important to keep trying and experimenting with different activities that’ll make you want to get up in the morning again.”

“Not everyone breaks through to phase four,” Moynes concedes, “but those who do are some of the happiest people I have ever met. Phase four is a time to reinvent and rewire. But phase four involves answering some tough questions, too, like, what’s the purpose here? What’s my mission? How can I squeeze all the juice out of retirement? You see, it’s important that we find activities that are meaningful to us and that give us a sense of accomplishment.”

Nothing terribly profound, I’ll admit, but for those of us contemplating or in retirement, I think this framework is useful.

And it dovetails with long-running, formal research on well-being regardless of life stage. Martin Seligman, in his 1998 inaugural address as head of the American Psychological Association, took the opportunity to “shift the focus from mental illness and pathology to studying what is good and positive in life.”

Over time, he developed and validated the so-called PERMA model, which includes the following five skills that help people thrive (and they seem to echo elements of Moynes’s phase 2 above):

Positive emotion: “Within limits, we can increase our positive emotion about the past (e.g., by cultivating gratitude and forgiveness), our positive emotion about the present (e.g., by savoring physical pleasures and mindfulness), and our positive emotion about the future (e.g., by building hope and optimism).”

I can see the eye-rolling, but Seligman adds this caveat: “Unlike the other routes to well-being described below, this route is limited by how much an individual can experience positive emotions. In other words, the experience of positive emotion is partly heritable, and each individual's emotions tend to fluctuate within a range. … so it can be liberating to know that there are other routes to well-being, described below.”

Engagement: “Engagement is an experience in which someone fully deploys their skills, strengths, and attention for a challenging task.”

Relationships: “The experiences that contribute to well-being are often amplified through our relationships — for example, great joy, meaning, laughter, a feeling of belonging, and pride in accomplishment. Support from and connection with others is one of the best antidotes to ‘the downs’ of life and a good way to bounce back.”

Meaning: “A sense of meaning and purpose can be derived from belonging to and serving something bigger than the self.”

Accomplishments: “People pursue achievement, competence, success, and mastery for its own sake, in a variety of domains, including the workplace, sports, games, hobbies, among others. People pursue accomplishment even when it does not necessarily lead to positive emotion, meaning, or relationships.”

So, maybe, Seligman’s PERMA model + Moynes’s roadmap = rewarding retirement?

By the way, does anyone here suffer from lower back pain?

4) Lifelong Learning

I recently enrolled in an adult education class on 20th century American short stories. Actually, I initially signed up for a course on Moby-Dick but quickly dropped it because the book was too dense for me, and, frankly, it has always bothered me that the whale’s name is hyphenated.

The short story class was pretty good (John Cheever, E.B. White, Flannery O’Connor, et al.), but I probably was the youngest participant by 15 or 20 years. So, I decided to head in the opposite direction by auditing an undergraduate course on the history of human genetics at Johns Hopkins University, where I likely was the oldest by 40 years.

On the first day of class, the professor asked the 25 or so students to introduce themselves, state their major and year of matriculation, and explain why they had chosen the course. There were many juniors and seniors, some with majors like biostatistics and molecular biology.

When it was my turn, I said, “I’m a senior — pause — of a different sort.” Not my best work, I’ll admit, but I got no reaction at all. Tough crowd, very studious.

The syllabus covered topics ranging from classical genetics such as Mendel’s peas, Galton’s theories of heredity, and sex determination in fruit flies to contemporary subjects such as recombinant DNA, genomics, and biomedicine. I understood maybe 20% of the reading1 but was able to follow many of the robust class discussions, particularly when they involved bioethics.

I was also reminded of the following:

Why I was not pre-med in college

The value of diverse viewpoints in discussing challenging issues

How stunningly impressive college faculty can be in the command of their subjects

The torture of sitting in class for three hours, especially in Medieval writing tablet chairs

Did I mention I’ve been having some back pain?

3) What Comes After Retirement?

Last year, Sebastian Junger, the author and war correspondent, perhaps best known for his book The Perfect Storm, published In My Time of Dying. It’s an account of his near-death experience from a ruptured aneurysm, which included a vision of his late father as he slipped away. “It’s okay,” his father said, inviting Junger to join him. “There’s nothing to be scared of. I’ll take care of you.”

I listened to a podcast interview with Junger, who tries to make sense of what happened to him in the ER.

He wrestles with “whether or not you think it was just a neurochemical experience that I was having in my brain, my brain was just hallucinating … or if you think that there was something sort of mystical, something other going on that reveals a deeper secret of the universe, that there’s some life after death. … Whichever way you want to look at it, and I’m kind of agnostic about it, either way it was maybe one of the closest moments I’ve ever had with [my father].”

While I found Junger’s account of his brush with death intriguing, the second half of his interview moved me even more. Junger, now 63, talks about the importance of community and civic duty; helping others “live with more dignity and less fear”; finding the humanity in one another, especially in trying times (“what happens to you, happens to me”); and finding “deep purpose” in life (in his case, raising and comforting his young daughters, the first of whom was born when he was 55).

Rather than try to sappily link these themes back to Seligman and Moynes, I suggest you give the podcast a listen. I did so at 1.75x speed while racing, not meandering, north on the New Jersey Turnpike. I’ve listened to fewer than 10 podcasts in my life, so I might not be a very good judge of the medium, but I found Junger’s insights compelling.

2) Sidetracks

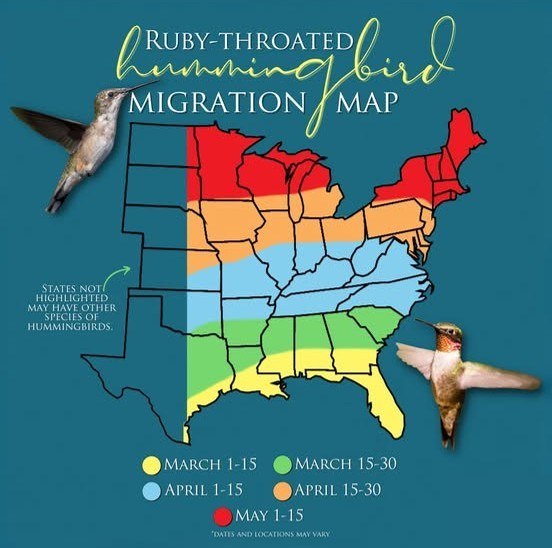

For those of you who live on the East Coast (Meandering Tour, by the way, has subscribers in Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Utah, among other non-coastal locations), the approximate date to start feeding hummingbirds is fast approaching.

In other hummingbird news, there’s a new nature documentary, called Every Little Thing, about a hummingbird rescue organization. It’s inspired by Terry Masear’s 2016 book, Fastest Things on Wings. “It’s a straightforward premise for a film,” writes a reviewer for The Guardian. “But life, as Masear tells us at one point, is a series of metaphors stacked up on top of each other, and so it is with Every Little Thing. It’s a shimmering, densely layered film about love and resilience, about how we live with and recover from trauma, and about letting go.”

You’ve heard of MoMA, of course — the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Turns out there’s a museum in Belgium called MeMa, which stands for Meandering Museum Antwerp. No relation.

Principle of the Week: The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias in which people with limited competence in a particular field overestimate their abilities. In other words, you might want to consider unsubscribing to this Substack.

1) Toast Point

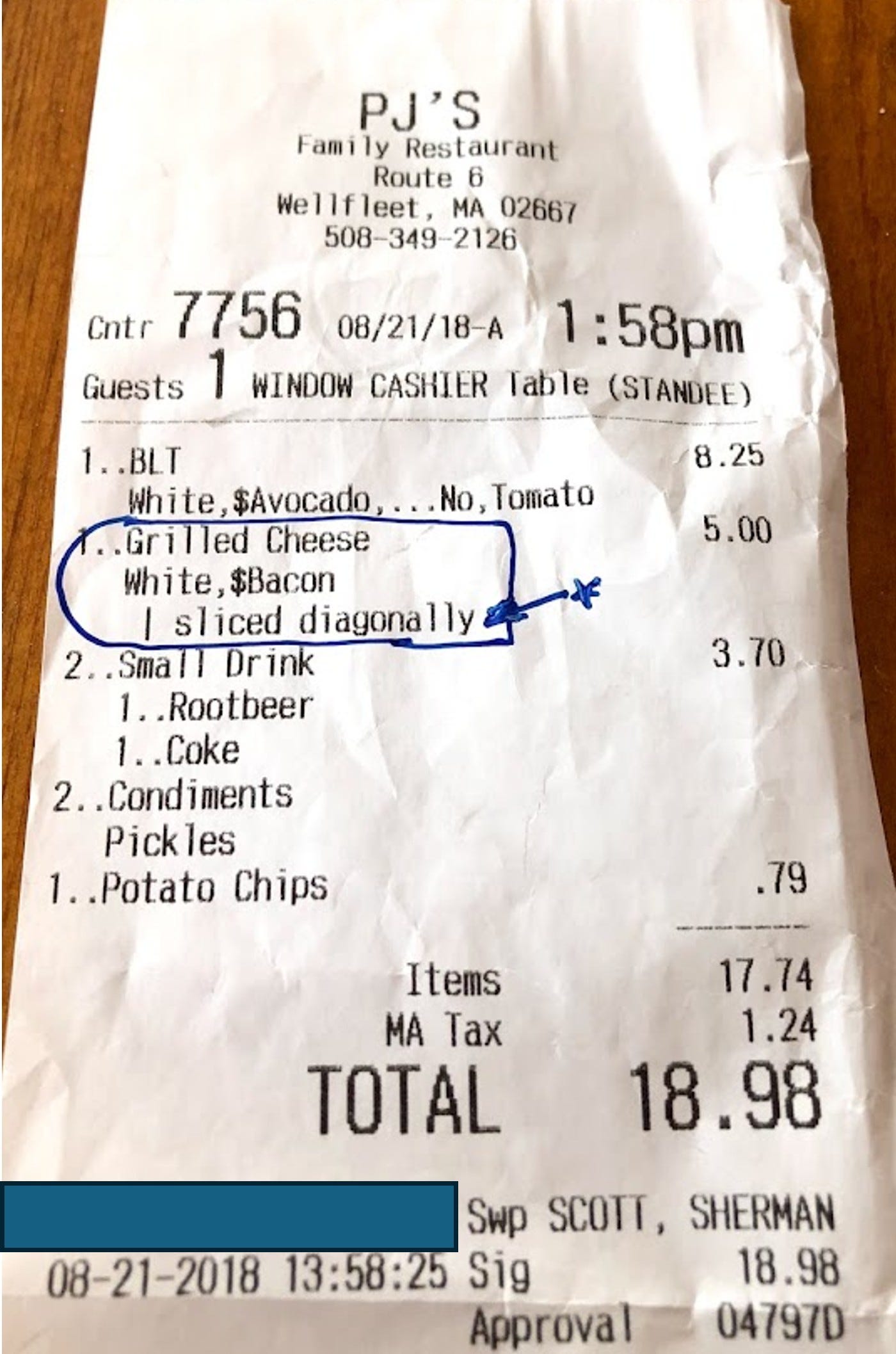

“The Mezzanine” (1988) is the first novel by American writer Nicholson Baker. Virtually plotless and filled with footnotes (including a footnote about footnotes),2 it’s the stream of consciousness of a man who’s riding an escalator in an office building during his lunch break. One of my favorite passages is when the narrator emphasizes the importance of cutting toast diagonally.

Now, why was diagonal cutting better than cutting straight across? Because the corner of a triangularly cut slice gave you an ideal first bite. In the case of rectangular toast, you had to angle the shape into your mouth, as you angle a big dresser through a hall doorway: you had to catch one corner of your mouth with one corner of the toast and then carefully turn the toast, drawing the mouth open with it so that its other edge could clear; only then did you chomp down. Also with a diagonal slice, most of the tapered bite was situated right up near the front of your mouth, where you wanted it to be as you began to chew; with the rectangular slice, a burdensome fraction was riding out of control high on the dome of the tongue.

I have no way of proving this, but I swear I came to this very same conclusion on my own (see receipt below).

I’ve been trying to find a way to add a footnote to my Substack (you’ll see why, later), and this is my opportunity. I found much of the course reading very difficult and often impenetrable, as I do not have a science background. One assignment, which I was able to handle, was a lay publication: a 1975 Rolling Stone article about a now famous conference of 140 scientists who met at the Asilomar Conference Center on the Monterey Peninsula to draft safety guidelines for DNA research. The participants issued a letter, “Potential Hazards of Recombinant DNA Molecules,” that called for a moratorium, apparently still largely respected today, on certain kinds of gene transfers between different species.

Nearly 50 years later, the author of this very same Rolling Stone article, Michael Rogers, published an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times about a similar event — a letter issued by leading artificial intelligence researchers, who called for a moratorium on some AI projects, warning of a possible “AI extinction event.” The March 2023 letter, titled “Pause Giant AI Experiments,” proposed that AI labs “immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4.”

I am by no means an expert in this field, but it appears to me that the researchers’ advice was not followed, e.g., DeepSeek. But if any experts are reading this footnote, would you please comment. Actually, if anyone is reading this footnote, please raise your hand in the comments section, and you’ll get a special mention in next week’s column.

Please read my own footnote 1 above regarding the genetics course I audited.

Scott - As a reformed lawyer you should know that footnotes often contain the most important points in a case! I can’t help myself — I read all of them! Really enjoy your posts. I think you may have found your calling, at least until you audit your next class in quantum physics!!

Not for nothing, but out of the exactly 10,450 words you have published to date on this meandering tour, nothing has revealed as much about you as the fact that you held onto - AND COULD FIND - a Massachusetts diner receipt from seven years ago. Discuss among yourselves.